We are all in this vast landscape that is life, on a journey toward the discovery of ourselves and others. That’s why a road trip can easily become a metaphor for human life. There is something left behind and a future that is coming. Some know their way, others just wander. The trip has been a prolific theme in the universal narrative because it allows the random, the multiplicity of characters and settings. Not by chance “The Odyssey” is the most influential work in history.

Cinema, by being a succession of moving images, can be compared to an extensive road, where as spectators we travel to a final destination. The origins of road movies came from mythical epics but also as a progression of the western genre, where the horse was replaced by the car. Others consider that it was born with Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road.” Undoubtedly, it became visible as a genre with “Easy Rider” (1969) although it had emerged a long time before films like “It Happened One Night” (1934) or “Wild Strawberries” (1957), but no one considered them examples of a new genre because they fit in with others.

The consecration of road movies was achieved with the ‘60s counterculture where all manifestations pointed to the same objective: breaking with the status quo and old traditions to proclaim freedom of expression. The road became a means of escape, to leave behind the ghosts of war and move toward a new beginning in an improvised experience. Migrations and escapes made by cars, trains, airplanes, buses or ships. We must understand that this genre can easily escape from its common space by adapting to the different socio-economic development of each country. In this way, it’s a legitimate wandering made by foot or a road movie off-road.

This list searches for films that transgress the American road movie archetypes, proposing an avant-garde form with nonlinear narratives, free montages, dissonant sound worlds, and stylization of image. We are in front of a combative cinema facing its worst enemy – conventionalism – and attacking it with experimentation and authenticity.

1. Pierrot Le Fou (1965, Jean-Luc Godard)

The tragic and misfit Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo), after being fired from his work and disgusted by the frivolity of the world around him, embarks with Marianne (Anna Karina), a childish femme fatale, on a romantic getaway breaking all laws, even those of cinema. Among guns, books, musical scenes and tragedy, this duo will face the impossibility of love.

Based on a crime novel and born in the middle of Godard’s breakup with the main actress, this film becomes a mirror of the love betrayal he had to face and also his own struggle in the research for a unique style.

Godard breaks the narrative logic with a fragmentary mise-en-scene, as a collage, with inserted frames of magazines, paintings, vignettes, and handwriting, using an introspective voice-over and a discontinuous soundtrack to make the viewer aware of the subjective nature of creation. Brecht’s groundbreaking style direction, the combined color palette, the jump of axis and ellipsis, the documentary and theatrical tone, the welter of genres, and infinite references that go from pop art to Velazquez, converge in an authentic experimental work.

Godard in this film (or in his own words, “in this attempt to make a film”) plays his most subversive weapon, rejecting the verisimilitude.

2. Touki Bouki (1973, Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Mory and Anta, an unhappy young couple from post-colonial Senegal, dream of fleeing to Paris on the next ship. They ride the streets of Dakar by motorcycle, plotting a plan to reach the other side of the ocean. After stealing money, they buy the tickets. But when the ship is ready for departure, Mory’s ghosts around his childhood and homeland will appear. Is Paris the Promised Land?

Mambéty laughs at frivolity, showing how the young couple fantasizes about power and recognition, in a key scene where they both parade in a car, adopting an extravagant personality and being praised by the neighborhood that previously used to hate them. “Touki Bouki” exposes the clash of two contradictory cultures that, when merged, cause the division of the members of a society, between those who value their own and those who desire what is foreign.

This film is a hybrid between African traditions and Nouvelle Vague. The free and associative editing incorporates a cyclical vision that breaks with linear narrative. The director claims to be a griot (an old African poet who tells stories) but is also strongly influenced by Godard, in the pictorial of color and sound dissonance. Seagulls and the sea collide with the ironic soundtrack with the song “Paris, Paris.”

Poetic and political, “Touki Bouki” shows us the misfortune of thousands of young Africans who seek luck in Europe, but only find mistreatment and death.

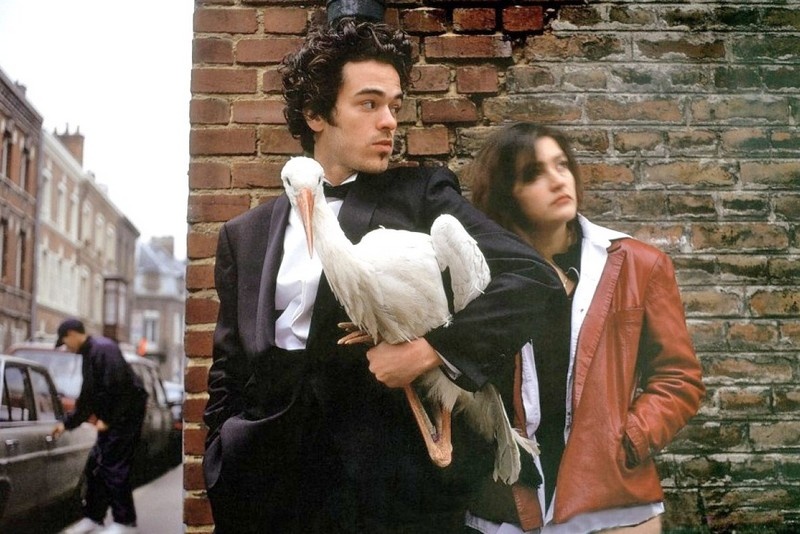

3. The Children of the Stork (1999, Tony Gatlif)

Otto, an unemployed young man who sells newspapers, and Louna, a crazy and exploited hairdresser, both tired of having no hope in future, join to hit the road next to Ali, an intellectual boy who escapes from his family’s attempts to hide their Muslim roots.

Paris is polluted and starved, but this anarchic trio rebels against capitalist society by stealing cars and burning whatever they cross. On the way they will find a stork with an injured wing who will ask them for help to cross the border with Germany. The stork, being a migratory bird, works as a metaphor for the problem of immigration and borders.

Gatlif took a risk with this eccentric road movie where the narrator laughs at the characters, with sharp jump cuts, ellipsis, and sound collages, reminding us of Godard’s innovations in the ‘60s. Far away from his gypsy theme, this journey of mischief is perhaps the strangest thing in Gatlif’s cinema, but his usual characters remain: nomads who have nothing to lose but their chains.

Otto, Louna and Ali are like storks, free birds that will always be foreigners because they don’t care about conventionalist existence. And they have no other home than a nest in the roof.

4. Walkabout (1971, Nicolas Roeg)

From the bricks of a facade to a desert, from citizens locked to fulfill an established role to the messy stones of a vast open ground, we are in front of a clear confrontation between white civilization and barbarism.

Two children are abandoned in the desert. Without water and food, they must survive in the Australian outback. Their null notion of survival doesn’t allow them to find a way out. It’s an aboriginal teenager who, in the middle of a ‘walkabout’, will save them. But they can’t communicate through language nor can they understand themselves by their opposite conceptions of life. Meanwhile, as the aboriginal child hunts to feed them, they insist on clinging to their occidental values.

Making a parallel editing through images of animals free in their wilderness and indiscriminate hunting, there are two cultures that meet. One that is interested in survival and the other only in commerce.

John Barry’s heavenly and exotic soundtrack joined to panoramic and detailed shots converge on this disorienting pilgrimage through the strange fauna of the Australian outback, where the cyclical spirit of nature feeds on death to sprout again and again.

5. Wild at Heart (1990, David Lynch)

Sailor and Lula must face the adversities of their love, being stalked by a controlling mother and perverted characters. Although this young couple embodies the archetype of misfits and rebels, Lynch breaks with the tradition of American road movies, adding surrealism. With unconventional editing that breaks linearity through flashbacks, parallels, and narrative ellipsis, Lynch offers us this twisted and modern ode of “The Wizard of Oz,” which looks more like a nightmare playing between the childish and sordid.