One is wont to mention auteur theory these days since the overuse of the term has been misappropriated to describe dilettantes shooting films on their I-Phones. The initial idea of the auteur was a director whose filmography exhibits a stylistic pattern specific to them. When talking about early films that foresee a director’s later style, there must be a thread of continuous elements specific to their cinematic vision. Such directors can comfortably be described as true auteurs.

The broadness of the topic casts a large net that captures films from a wide variety of decades and multiple genres. What is most impressive is the consistency of these directors. Elements and techniques from their earlier films ingeniously reoccur to share new ideas, drawing parallels in characterization and mood between two unlikely scenarios, yet the director’s sensibility remains the same. This touch of the director in every frame is the connective tissue that binds us to the beauty of cinema.

1. Alice in the Cities (1974, Wim Wenders)

The film that initiated one of cinema’s greatest partnerships between German director Wim Wenders and Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller, was also the first installment in Wenders’ road movie trilogy.

Two German expatriates, a journalist and a mother with her young daughter in tow, have an encounter at a New York airport before returning back to Europe. When they make it overseas, the journalist discovers the mother never boarded the plane, yet he has her daughter. The poor journalist discovers his paternal instincts and Alice, who has a surprisingly mature grasp on the severity of her situation, still cannot resist pining for American hotdogs. Characteristic of relationships that unexpectedly arise at stations and thoroughfares, the farcical pairing form a brief but memorable bond, as they tour around the northeastern pocket of northern Europe, hoping to return Alice to her grandparents.

Road movies are synonymous with a Wenders picture. Parts of his filmography of course explore other forms, some of which are not easily pinned down into classifications, but he constantly reimagines the image of the road and the character who embarks on a journey across landscapes. Alice is unusual among Wender’s road movies, focusing instead on cityscapes. A notable example of this peculiarity is a shot of the sky-rail transit system in the German city of Wuppertal, which is beloved and of great fame among Krauts.

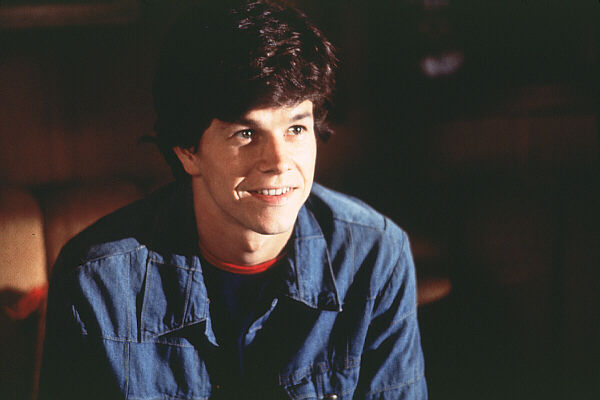

2. Boogie Nights (1997, Paul Thomas Anderson)

When Paul Thomas Anderson released Boogie Nights at the age of only 27, he became Hollywood’s new wonder-kid. Set in Anderson’s native San Fernando Valley, an unremarkable Eddie Adams runs away from his unloving mother to the open arms of a porn director Jack Horner. Jack appreciates and has a vested interest in Eddie’s only gift: his legendary sized penis. Such a preposterous premise anticipates the outrageous events to follow, as Eddie reinvents himself as porn star Dirk Diggler, and him, Jack, and their inner circle rise to the top of California’s seedy porn industry. Their rise as celebrity porn stars eventually comes crashing down as their fast life lifestyle and drug fuelled hedonism catches up with them.

At an approximately two and a half hour running time, Boogie Nights is a precursor to Anderson’s next film, the interweaving multi-narrative epic Magnolia. Striking the balance between entertainment and intellect, Anderson uses the bildungsroman as an entry point to turn his critical eye on celebrity culture, the fallibility of the American Dream, and strained familial relations. The latter film expands on these same themes, but with biblical and mythological undertones that feature with clearer focus in 2007’s There Will Be Blood.

Each of these films cast a grim shadow on uninhibited individualism, the subsequent greed that flows from it, and the violent consequences when too much is never enough.

3. Camera Buff (1979, Krzysztof Kieślowski)

For anyone diving into the acclaimed works of Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski, namely The Double Life of Veronica and The Three Colors Trilogy, but are struggling to grasp exactly what the director is up to, then please watch Camera Buff. In no other installment of Kieślowski’s filmography does he clearly depict the idea that one’s actions has an incidental unforeseen impact on the lives of others, whether they know it or not, and one must be prepared to take responsibility of those effects, especially when they are deleterious rather than positive as intended.

The protagonist is a factory worker named Filip, who is an amateur filmmaker who wants to create a film for the common Pole, eventually making a documentary about the daily lives of his fellow coworkers that earns him much renowned. For his friends the popularity of the documentary strains their relationship with the factory’s owner. Filip’s fascination with the art of film consumes him, wanting to capture all of life’s moments on camera, raising the moral question of whether there isn’t anything too precious or personal to film.

Camera Buff marks Kieślowski’s transition into feature films, so it is only natural that he draw from his prior experience as a documentary filmmaker. It is a barbed perspective on the potential evils of the art form of cinema, and has a clairvoyance that anticipates the fundamental problems of Kieslowski’s future protagonists.

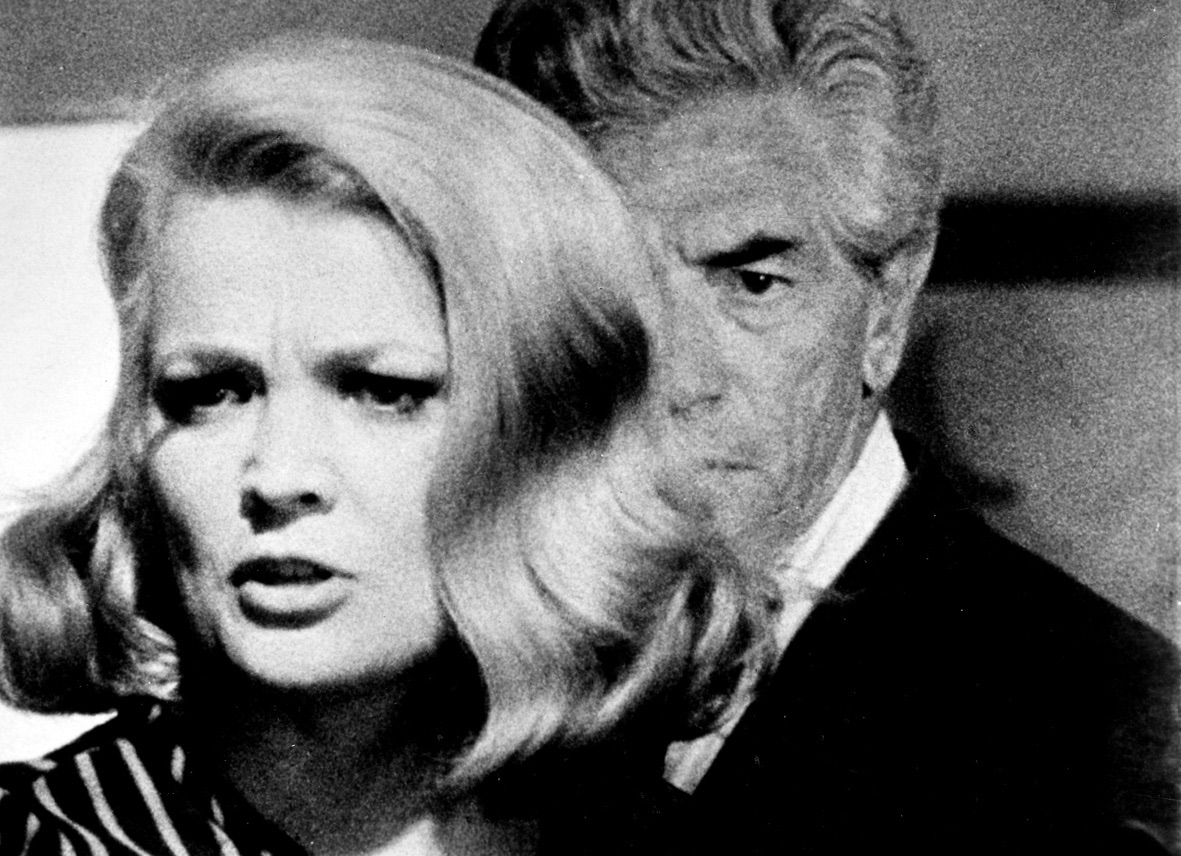

4. Faces (1968, John Cassavetes)

One of the best examples of portrait photography ever committed to celluloid, John Cassavetes passion project Faces is as tender as the night. It took several years to film because Cassavetes would run out of money and have to return to acting, ripping off Hollywood as he would more or less put it (his feature in Cinéaste de Notre Temps comes highly recommended), so he could continue work on the film. But besides championing the independent cinema movement, the cinematographic techniques on display and pacing characterize the actor/director’s subsequent work.

As the characters work through infidelity and doomed matrimony, rather than cut away as other films would, Cassavetes prefers to zoom in on his character’s faces, pondering their expression in moments of silence, laughter, hysteria, sadness and love. There is an empathy for the characters rarely seen elsewhere except for other Cassavetes’ films. Part of his patience for the characters is also because he encouraged his actors to drift from the script if it was for the sake of naturalism, so he gives the actors time to work and the characters space to feel. His next film, Husbands, applies that principle to a further extent to mixed results depending on who you talk to. Even his last film Love Streams, dwells on the faces of its characters with the sensitivity of a parting glance, and is sometimes curious enough to zoom in as Faces likes to do so often.

For Cassavetes, whether people enjoyed his films was irrelevant. His aim was to create “Art, meaning we can live and express ourselves freely.”

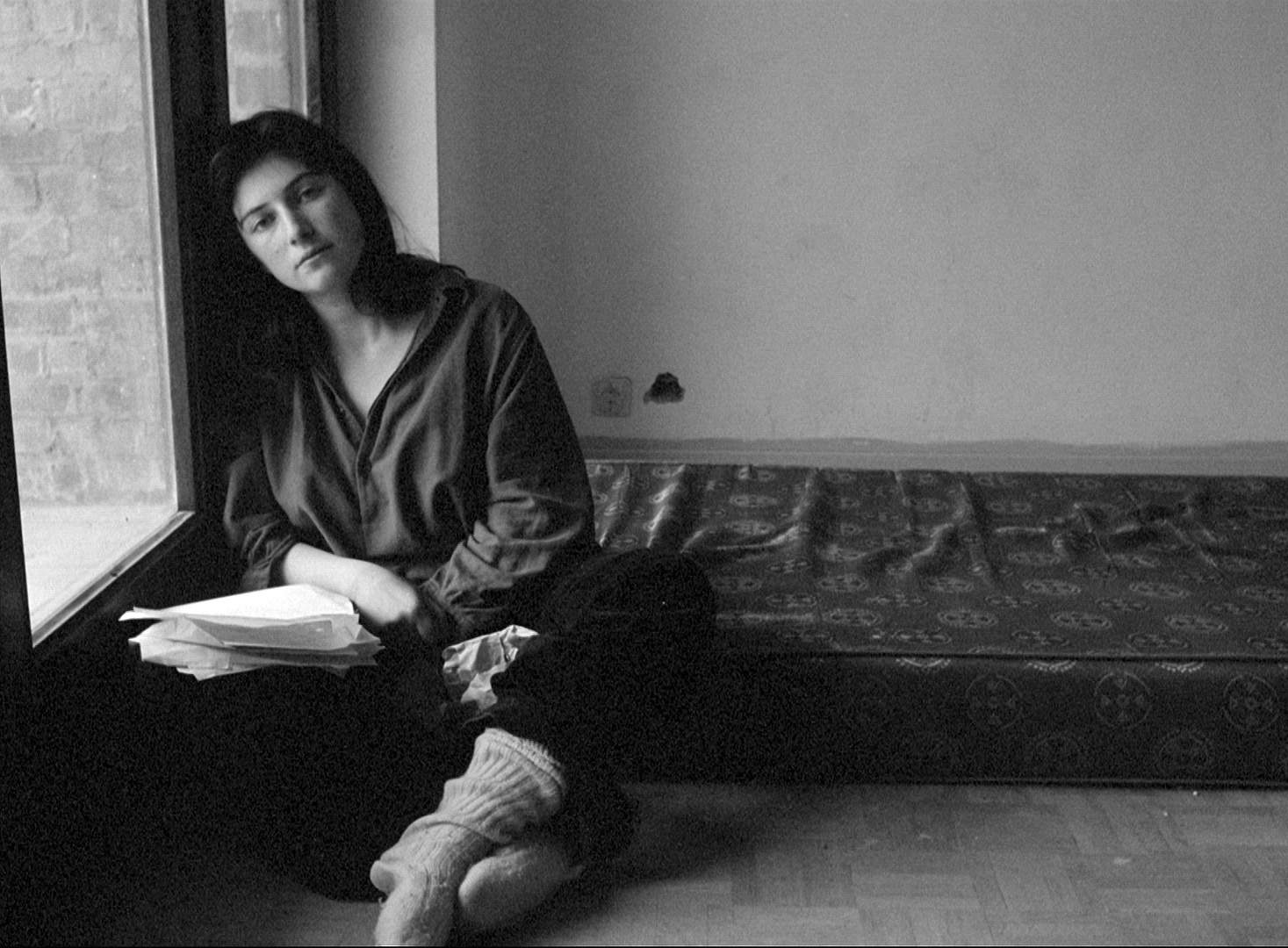

5. Je tu il elle (1974, Chantal Ackerman)

An admittedly oppressive film to watch, if not for the oppressively long takes and silence of the main character Julie, then for how she only eats spoonfuls of sugar to sustain herself during her ascetic style self-imposed isolation. Belgian director Chantal Ackerman relinquished the need to have much dialogue in her films, or at all as in From The East, letting the image speak for itself. Swaths of the film depict Julie rearranging her furniture, searching for new ways to find comfort so she can settle into writing, though nothing fully satisfies. These scenes contain voiceovers of what Julie’s writing, describing her listlessness, self-perception, fatalism, and sexuality, all of which play out in both discreet and explicit forms in the film’s second half.

This exploration of the life of a young woman parallels with Ackerman’s next feature, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai de Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, having a middle-aged housewife as its subject. Both are female centric films that have a fascination with structural concepts of how space evolves over time, and how that evolution has a corresponding change on the film’s characters. For this reason, the camera is often static, or if there is movement, it is minimal so the sense of space is not lost. Usually Ackerman will opt for selecting different zoom lengths rather than move the camera, or simply choose another angle to perceive the action, then step away from the camera and let the action unfold over a long take. These two films solidify Ackerman as an originator of feminist cinema and one of the most cerebral directors of her time.