Almost by its very definition the horror genre has to be bizarre. In order to scare horror must stray in some capacity from the safety of the norm. Whether it is to the extent of creating fantasy worlds and unnatural monsters to presenting human killers based on true events, horror brings a brush with the bizarre to plunge the audience into a world that they either can’t, or don’t want, to comprehend. The outlandish content of the horror genre also gives filmmakers liberty through its form, allowing directors to make bold and shocking creative choices to provoke the most visceral reactions possible in audiences.

Ultimately, as creative boundaries are continually pushed and experimented with, horror films are produced that are more and more bizarre to elicit as extreme reactions in audiences as possible. It is a fine balance for filmmakers to know just how far into the weird to go without alienating or outraging too many people. Even if a filmmaker’s intention is to shock and bewilder their audience, is still has to be somewhat legible to enough people to gain popularity and make money. When they are at their most successful, horror films that could be at first considered confusing and outrageous can become some of the most influential of the genre by revolutionising narratives, establishing new codes and conventions and making a lot of money in the long-run.

The films on this list walk the fine line between revolutionary and nonsense on a razors edge as they are some of the most extreme and crazy films to be hailed by horror fans and accepted by portions of wider mainstream audiences and critics alike.

10. Nightbreed (Clive Barker, 1990)

Despite having only directed three feature films, Clive Barker is undeniably an auteur of the horror genre. His films are so thematically and stylistically unique he can almost be categorised as establishing his own sub-genre of horror of highly-sexualised, sado-masochistic films featuring gruesome monsters, sinister demons and extremely graphic violence. His 1987 feature debut, Hellraiser, is arguably one of the most iconic horror films of all time, with a vast number of even non-horror fans being able to recognise Pinhead and the puzzle cube. Hellraiser itself could easily be included on this list; however, it is Barker’s lesser-known sophomore film, Nightbreed, that, although not competing with Hellraiser as an overall film, gives it a good run for its money in its bizarre content.

Based on his 1988 novella Cabal, Nightbreed follows Aaron Boone, a young man who is led to believe that he is a serial killer by his psychiatrist, Dr Decker, expertly played to a frightening degree by horror-auteur in his own right, David Cronenberg. On the run from the police, Boone hides in an abandoned cemetery where he finds himself among a community of monsters, the Nightbreed, who can only come out at night and have been driven away from society by the violence of man.

The Nightbreed are made up by a troupe of disturbing and sickening looking mutants beyond description, notably a banana-shaped headed man that looks distractingly like Robbie Rotten from the children’s TV show Lazy Town. However, despite their appearance, this tribe of outsiders and misfits are not the villains of the film, instead embodying figures of sympathy who have been victimised and excluded by the hatred and violence of humans. Mankind are the real monsters of the film as they take hyperbolic glee in battling and murdering the mutants in the final act of the film, relishing the opportunity to use as brutal and sadistic weaponry as possible. Considering Barker’s homosexuality, it is interesting and apt to assume a queer reading of Nightbreed with the mutants representing the LGBTQ community who are seen as freaks and monstrosities by mainstream society to the point of violence and murder.

This main narrative involving an underground society of beasts is already bizarre enough to compete with Hellraiser to be included on this list; however, it is the inclusion of Cronenberg’s psychotic psychiatrist that really gives Nightbreed the edge. By gaslighting Boone into believing that he is a serial killer, Decker covers for his own spree of vicious murders that he enacts throughout the film, clad in a terrifying skin-tight mask with buttons for eyes and a zip for a mouth. Decker is a cold, sadistic maniac that relishes in butchery and torture that, after the first half an hour or so of the film, really isn’t integral to the plot of the story until the end, but he forces himself in with an iron will and a steel blade.

Nightbreed could have very easily existed without the character of Decker at all but it is to Barker’s insane brilliance that he is. In the final showdown with the mutants, Decker doesn’t seem to have a particular hatred for the mutants, seeming to just be in it for the blood and carnage of it all, as well as now having a personal agenda to kill Boone. Cronenberg plays Decker perfectly as an ice-cold psychopath almost surpasses any of his own films in its scariness.

Nightbreed is by no means close to being a masterpiece and its extreme campiness can be at times laughable but it is definitely a bizarre experience that is perfect to watch late at night with a group of friends and a bunch of snacks.

9. Phenomena (Dario Argento, 1985)

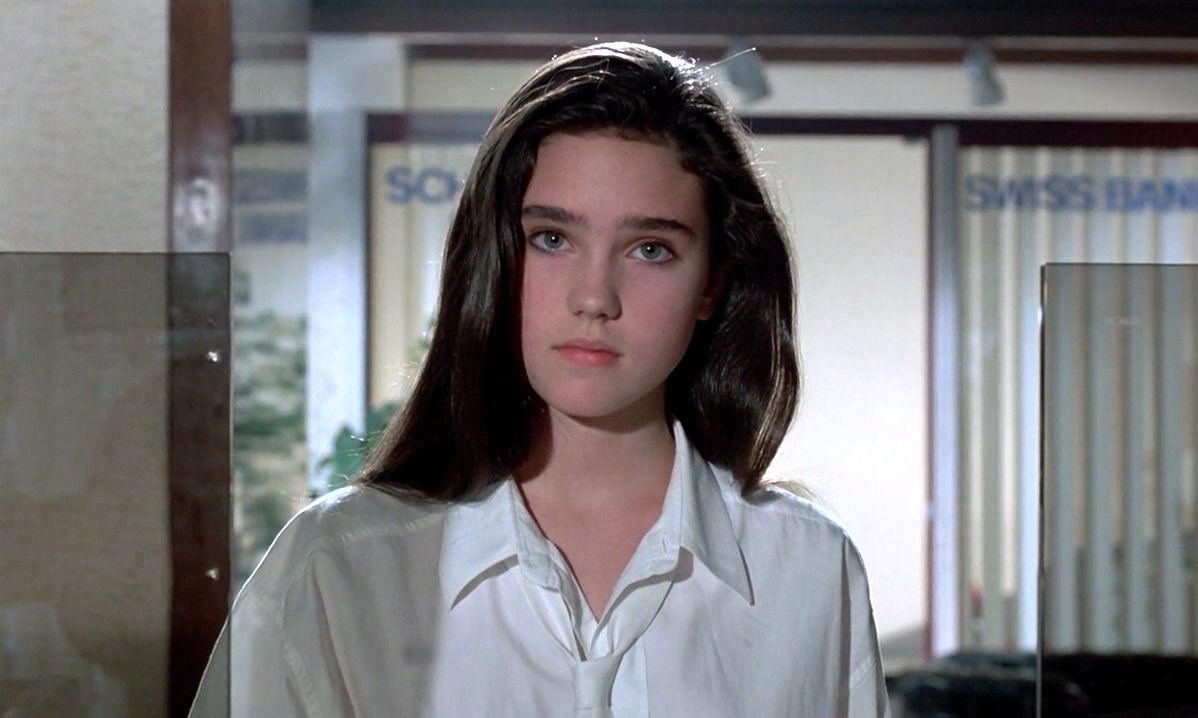

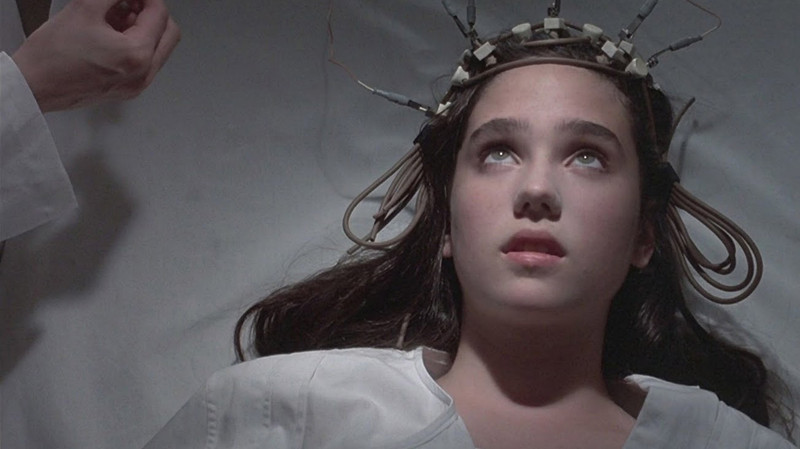

Dario Argento is one of the most revered cult horror directors of all time, producing such classics as The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Deep Red and Suspiria. Argento’s films always flirt with the bizarre, featuring covens of witches, psychotic killers and shocking twists, but never before has he gone so successfully crazy than in his 1985 picture Phenomena. Jennifer Connelly stars in her first leading role, having only previously appeared in Once Upon a Time in America (directed by friend and collaborator of Argento, Sergio Leone), as a young girl at a new school in the hills of Switzerland with the ability to communicate with insects. Meanwhile, a series of brutal murders plague the small Swiss community which can only be solved by Connelly and her six-legged friends.

Combining the psychic themes of 70’s Brian De Palma films with his classic Giallo touch, the vague synopsis of Phenomena already sounds like one of Argento’s wackiest pictures yet. Now insert horror acting royalty Donald Pleasance as a paraplegic, Scottish entomologist and his Chimpanzee helper, Inga, and an insane final act that features a decomposing pit, aquatic blaze and the reveal of why the killer’s house has all of its mirrors covered.

There seemed a slight obsession in the mid-to-late 1980’s with monkey butlers helping the disabled in horror films as only three years later another of Argento’s friends and collaborators, George A. Romero, would broach the subject in his equally bizarre Monkey Shines. Meaning no offence to any of the cast involved, which does include a future Academy Award winner, Inga is the real star of the movie as she pushes around the incapacitated Pleasance, clings to the roof of the killer’s car and can be seen as the moral centre of the whole film. Unfortunately, behind-the-scenes troubles with lead actor Connelly stunted Inga’s career as she was consistently uncooperative on the shoot, at one point even reportedly biting Connelly. Another bright acting talent thrown onto the egoic bonfire.

Perhaps most bizarre of all is Phenomena’s soundtrack (yes, more bizarre than the monkey butler) to the point of the film’s detriment. Although a lot of the film is scored suitably by Goblin, Argento insists on littering the film with random and needless heavy metal songs from Iron Maiden and Motorhead. In their own right these songs are perfectly fine but are more than jarring when employed over the footage of a corpse being solemnly stretchered out of a home or Connelly trying to escape from the killer’s house. At least if Argento had used an iron maiden as a form of torture it could have made at least a slight bit of sense. Of course, the narrative never warrants the use of such torture, but when has that ever stopped Argento before?

8. In the Mouth of Madness (John Carpenter, 1995)

Arguably John Carpenter’s most underrated film, In the Mouth of Madness is an existential nightmare in which insurance investigator John Trent (Sam Neill) is hired to look for missing horror author Sutter Cane, whose disappearance is as mysterious as one of his own stories. Convinced that Cane’s disappearance is nothing more than a publicity stunt for his upcoming novel, Trent’s investigation proves that Cane’s book is going to be all the craze. . . in the worst ways possible.

Carpenter combines a Lovecraftian mythos with a Stephen King inspired atmosphere and Clive Barker-esque fantasy to create a literary Frankenstein in which all of the most monstruous parts are stitched together for the screen. Trent’s investigation leads him, along with Cane’s editor Linda, to the sleepy town of Hobb’s End in which the lines of Cane’s pages and reality blur; a place where murders and events from Cane’s fiction suddenly seem to be not-so-fictitious.

Determined not to fall for any tricks, Trent is resistant to any possibilities of the supernatural while Linda begins to assimilate into Cane’s community. However, once resistance is proven futile and evidence that what is happening is real abounds, questions of existence begin to whirl: if John and Linda are existing within a figment of Cane’s imagination, then what does that make them? Both an omnipotent creator and Devilish fiend, Cane reigns supreme over Hobb’s End in his church on the hill, typing his new novel that may be being released a lot sooner than anybody was expecting.

Trent’s return to “normality” coincides with the release of Cane’s new book: “In the Mouth of Madness”, featuring a protagonist and story that seems uncannily familiar. Furthermore, the book seems to be having a rather adverse effect on its readers that starts a breakout violence and carnage starts across America. Everyone loves being absorbed by a good book, but not this much. In the Mouth of Madness ends where it begins: with Trent depicted as the stereotypical image of insanity; his body and asylum cell walls decorated with scribblings warning about the danger of seemingly foolish fear. John has been well and truly chewed up and spat out by the Mouth of Madness and now it is the world’s turn too.

7. Tetsuo: The Iron Man (Shinya Tsukamoto, 1989)

Feeling like it has come straight-off the assembly line and onto the screen with half of the factory fallen inside, Tetsuo: The Iron Man is a kinetic frenzy that follows the development of a man plagued by an affliction that causes his flesh to turn into metal. Presenting little more story than this, Tetsuo is an experiential, experimental film that clunks and scrapes the spectator through its short runtime.

Tetsuo is a post-industrial, nightmarish vision, filled with smoke and a chiaroscurist haze that makes it impossible not to compare with David Lynch’s 1977 masterpiece Eraserhead. The heavy metal soundtrack (in the most literal, non-Argento sense) clanks, whirs and scrapes the spectator through the film that, paired with the chaotic visuals and editing, means it is probably advisable to miss if you are prone to migraines. Combined with a Jan Svankmajer stop-motion style of visual effects, Tsukamoto creates a film that is owing in its experimental artistic influences but in no way can be accused of being derived.

Tetsuo opens with a man credited only as “Metal Fetishist” driving a metal rod into his maggot-infested thigh in one of Tsukamoto’s more subtle examples of metallic, phallic imagery. After being hit by a car and killed by a businessman and his girlfriend, the man’s penchant for metal appears to curse his killer with a twisted Midas touch in which, instead of being turned into gold, he is slowly and agonisingly turned into various metal parts. More phallic imagery ensues as the man’s penis is replaced by a large, whirling drill which he cannot control, much to the horror of his girlfriend. Seen through the scope of a bizarre domestic drama, Tetsuo reveals turning half-metallic and developing a huge drill as a penis can really put a strain on an otherwise healthy relationship.

Predictably yet still fascinatingly, the man continues to evolve into a metallic mess throughout the film until he is confronted by the resurrected, equally-metallic Metal Fetishist. Like Godzilla vs Mothra, the two monstrosities unleash their fury through the streets of Japan, at first on each other until they realise the vision of a post-apocalyptic, metallic utopia in which Earth shall be consumed by metal. You will likely only realise much of the narrative by reading a synopsis after watching it but story was never meant to be the appeal of this charged lightning bolt of a film.

6. Climax (Gaspar Noe, 2018)

The latest film on this list by over two decades, Gaspar Noe’s Climax is a claustrophobic, psychedelic nightmare of a film about a group of young dancers having a party after rehearsals at an isolated school. However, after they discover that their sangria has been spiked by LSD, a hallucinatory hell ensues. This film is an hour and a half long climax, pounding all of your senses so that once it has finished you feel like you are on a comedown.

Noe opens Climax by stating that it is “A French Film and Proud of it”; a bizarre and bold statement that sets the tone for the rest of the film as Noe unflinchingly presents the depraved and disturbing events that occur amongst the young adults’ panic. As they fight to find out who spiked the drink the group of dancers turn on each other while simultaneously turning in on themselves as the psychedelics affect their state of mind. The drugs unleash the madness and cruelty within these so-called partners, exposing people’s true feelings and the fragility of their professional relationships.

Never one to shy away from confronting audiences with brutal and graphic scenes, Noe challenges the spectator with issues of abortion and incest to make the viewing experience as uncomfortable as possible. Forcing the audience to feel as uncomfortable as possible may be thought of as a strange and risky trick for a filmmaker to play; however, Noe’s use of cinematography sucks the audience into the psychological chaos of the film, aligning you with the characters and making you believe that you cannot just turn the film off and escape. By utilising extensive long takes and a dynamic camera that is continually flipping, spinning and snaking through the building, Noe completely traps the audience in a perpetual state of anxiety. Make sure to cut your nails before watching this otherwise you will have very bloody palms.