Although contrary to simple intuition, repressive regimes often generate the most artistic expressions – perhaps, precisely because of their oppressive nature, which forces filmmakers to intellectually use humor, subtlety, and symbolism to present their view and critique society.

Francisco Franco’s 36-year dictatorship in Spain is no exception. Under his regime, which practiced great censorship of the film industry, a wave of filmmakers, including Luis García Berlanga, Juan Antonio Bardem, and Carlos Saura, rose to prominence and created a New Spanish Cinema. They revolutionized the film scene, bringing a host of dark comedies, art-house films, and poetic dramas to what was a stale industry of stereotypical, cookie-cutter melodramas.

Practically all of the films on this list are regarded as classic masterpieces of Spanish cinema and set the foundation for any Spanish film made after this period, making each of the following entries well worth the watch – even if you have to use subtitles. Those already familiar with Spanish cinema at this time will also be delighted to see José Luis López Vázquez, an actor often used as the prototype of the common Spanish man, appear three times in this list and twice more in the honorable mentions.

10. Mi querida señorita/My Dearest Señorita (1972, Jaime de Armiñán)

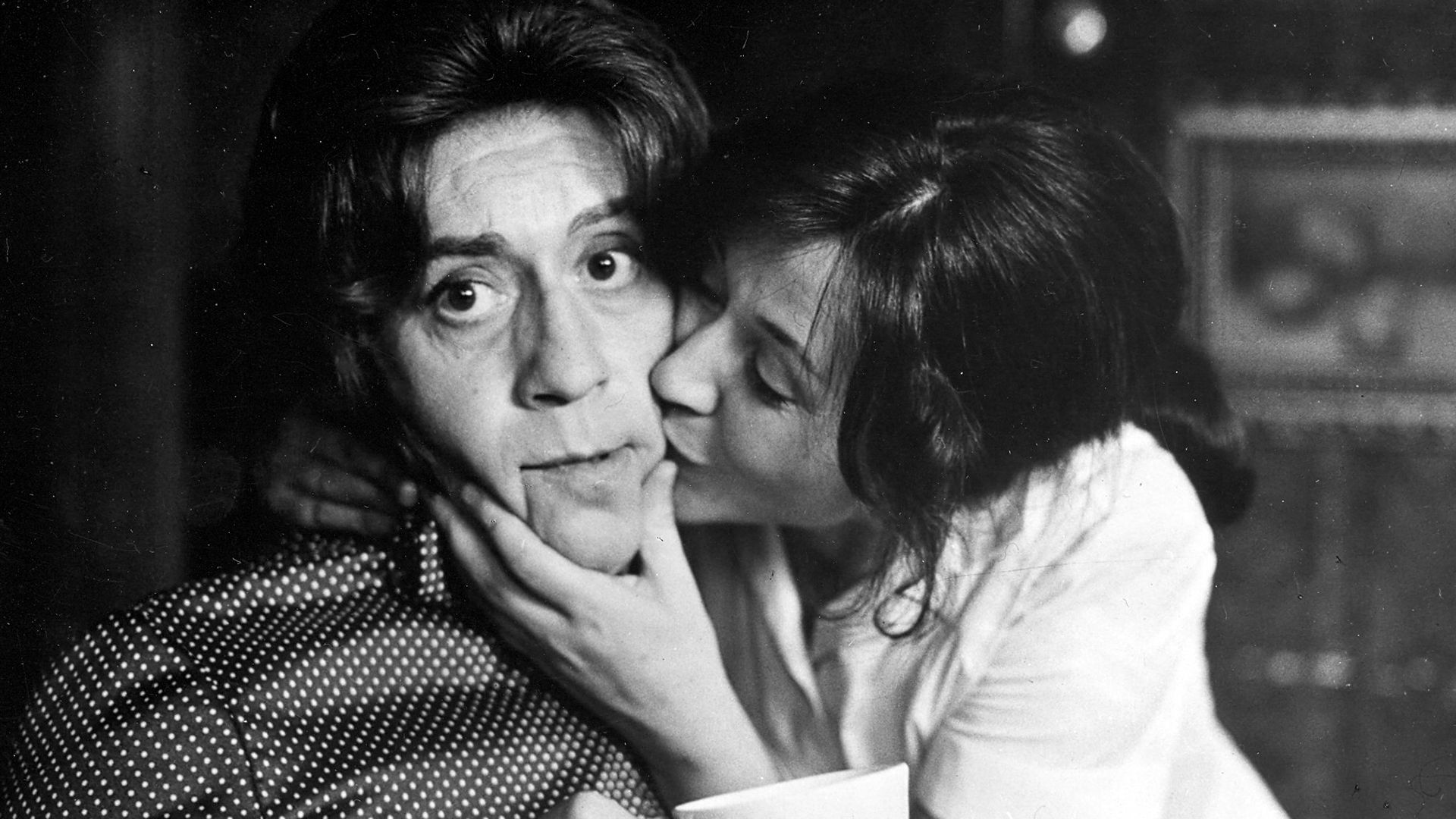

Released in 1972, the same year in which the suffrage rights of women became equal to those of men in Spain, My Dearest Señorita is the first Spanish film to focus on sexual orientation. Armiñán, whose filmography is full of characters on the margins of society and whose work aims at normalizing sexuality, collaborated with writer José Luis Borau to create this dark comedy about an elderly, unmarried woman named Adela moving to Madrid and adopting the masculine identity of Juan.

Because of the subject matter and the fact that it was quite taboo in Francoist Spain, José Luis López Vázquez, the star of the film, said My Dearest Señorita was the most dangerous job he has ever done. It is for this reason, however, that the film is so exceptional. The sensitive nature of its content pushed Vázquez into giving a virtuosic, yet subtle, performance, and the many challenges in which Armiñán had to go through in order to make the film are reflected in tasteful social critics.

Like most films made under repressive governments, My Dearest Señorita proves to offer something new – something you missed – each time you watch it. Not only does the film present critiques on strict gender roles and how societies based on dichotomies threaten singularity, but it also delves into themes of loneliness, the issues of integrating into modernity, the different challenges of provincial versus city living, and the collapse of the certainties of Francoism.

Ultimately, however, the film is about identity – the identities disguised during the dictatorship, the transformation and perhaps erasure of identities, and what Foucault called “the happy limbo of non-identity.”

9. La tía Tula/Aunt Tula (1964, Miguel Picazo)

Miguel Picazo’s debut feature film, Aunt Tula, also happens to be his most famous and well-regarded work from his four-decade-long career. Based on the 1921 short novel by Miguel de Unamuno, Aunt Tula offers a relatively simple dramatic plot, but Picazo’s delicate directing, Aurora Bautista’s utterly believable performance as Tula, and the film’s humble depiction of the rigid customs all familiar in Spanish culture offer a revealing glimpse into Spanish society.

The film follows a 31-year-old woman who takes on the responsibility of caring for her recently deceased sister’s children and widower, Ramiro. While she is completely loving towards the children and often caring towards her brother-in-law, Tula exhibits cold disdain and hostility towards Ramiro when he touches her and subsequently exhibits a desire to marry her.

Tula’s repressions reflect her religious beliefs and the strict social traditions surrounding her at this time. While casual American viewers may expect Tula to give in to Ramiro’s desires and provide the audience with a predictable ending, Picazo does not succumb to this troupe. Instead, he offers a more surprising close and leaves Tula essentially where she started – resigned to her unmarried life.

Although not the most well-known director on this list, Picazo’s classic film is worth the watch, and you can also catch him in a very small role as the doctor in The Spirit of the Beehive, which appears later on in this list.

8. El extraño viaje/Strange Voyage (1964, Fernando Fernan Gomez)

Originally a commercial flop, the “cult” movie Strange Voyage is now considered one of the best Spanish films of all time. Fernando Fernan Gomez, who is undoubtedly more well-known as a prolific actor whose career spanned over six decades, directed this film that blends aspects of thriller, suspense, black comedy, and noir to produce an absurd and morbid tale of three siblings who meet fatal ends.

The film was originally entitled The crime of Mazarrón, referencing the true events of the small village; however, Franco’s censors would not allow this direct reference to pass. Even so, Gomez conveys the story under the mysterious title of the Strange Voyage and manages to critique the hypocritical society under Francoist Spain.

Intelligently utilizing irony, humor, flashbacks, and a colorful ensemble cast, Gomez successfully reflects on the repressive nature of his characters and society at the time. Inspired by a conversation with Carlos Saura and in collaboration with Luis García Berlanga, Gomez draws on great minds to create this surprising triumph of a film.

7. La Caza/The Hunt (1966, Carlos Saura)

Carlos Saura’s first international success, The Hunt, borders the line between a simple hunting movie and a Spanish Civil War movie; however, at its core, the film is a psychological thriller of a place and a people inhabited by ghosts of the past. The story follows three middle-aged veterans of the civil war – José, Paco and Luis – and a teenage relative of Paco’s as they hunt rabbits in Seseña, a small province of Toledo. Each man enters the casual hunting trip with his own motives for meeting up and his own personal issues, which slowly unravel throughout the hunt.

At the time of its release, Spain started to open its borders and enter a period of economic improvement, but Saura’s intricately shot and masterfully slow-paced film proves that the Civil War, or at least its memory, has not been overcome in the 1960s. The film’s pacing combined with its setting – namely a sterile field that was the scene of a great massacre during the Civil War – render a stifling and oppressive atmosphere that aids in the depiction of the men’s mental decline.

One scene, in particular, lingers with the viewer until the film’s end: during a hunt, the men use a ferret to chase rabbits out of a tunnel. The ferret weaves through turns and crevices reflecting how the film explores the deep corners of the men’s minds. Then, when the ferret finally chases the rabbit out of the tunnel, Paco accidentally shoots both animals, heralding the death of the hunters by their own hand.

Like Alfred Hitchcock, Saura is a master of suspense in The Hunt and meticulously details the men’s psychological deterioration to the point in which the hunt becomes a reverse hunt.. As tensions and fears rise and manifest themselves into a cold-blooded fight, the hunter becomes the hunted, leaving the viewer with a shocking end and a need for reflection.

6. La cabina/The Telephone Box (1972, Antonio Mercero)

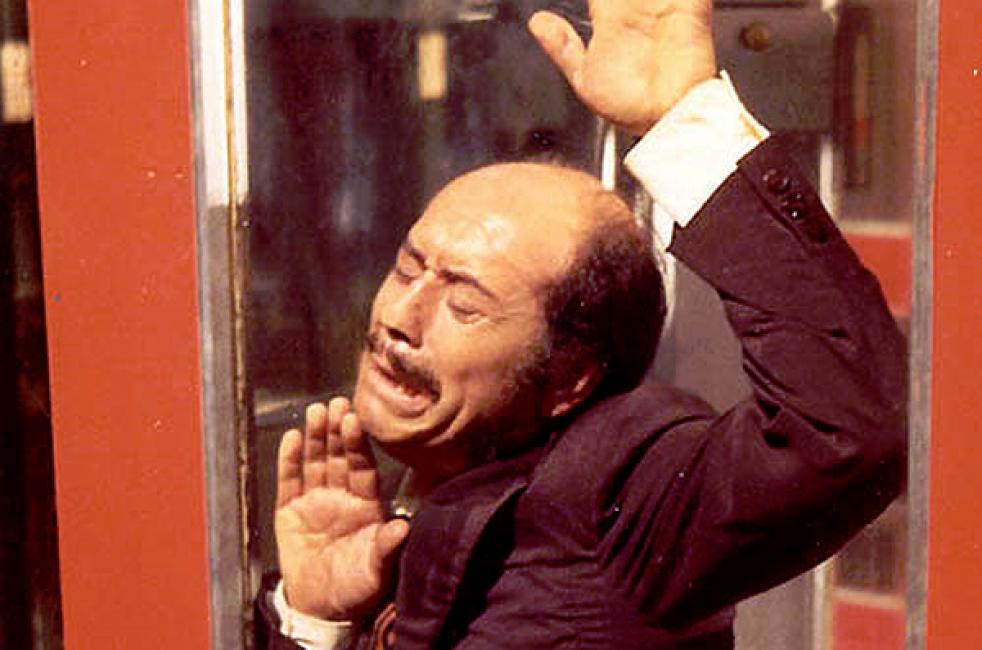

Made for public television, this short film of only 35 minutes and practically no dialogue may seem like nothing special at first glance; however, Mercero is able to convey more meaning in half an hour than many do in two. Financed by the state, The Telephone Box was originally intended to educate a changing Spain, as this film was released near the end of Franco’s regime. Although the film does depict modern city-life and Spain’s economic growth, it also illustrates the country’s dark underbelly.

The Telephone Box stars the ever so popular José Luis López Vázquez, who offers a compelling physical performance in this story of an average, suited man who becomes trapped inside a telephone box. Although there are many attempts, no passerby is able to help the man, and the seemingly innocuous box becomes a horrible nightmare.

Mercero presents his succinct story in three loose parts: the first introduces the film as a comedy and a social critic on Spanish society as the man gets himself into the absurd situation with the telephone box; the second reveals dramatic tension and suspense as he realizes he cannot escape; and the third turns the film into a haunting horror as the man – and the audience – finally realize his tragic end.

Any viewer of The Telephone Box will profess to its indelible, disorienting, and affecting nature. Perhaps, it is because the film echoes a common story of forced disappearances during the dictatorship or because it reveals Spain as a Buñuelesque society: a country that laughs at the misfortune of others, a society that takes advantage of its neighbor, and a neighborhood that is indifferent to a man’s cruel fate.