As this year’s awards season closes, there hasn’t been a bigger winner than Jane Campion. The New Zealand director came back in style after a decade-long hiatus with The Power of the Dog, a scathing meditation on masculinity, classism and idolatry set in the American frontier. Her latest rodeo at the director’s chair is more than just a return to form; it’s the cherry on top in an already indelible career. The film has been universally celebrated in the biggest stages, racking up an array of major awards and securing twelve Oscar nominations, more than any other film this year. Admittedly, this newfound appreciation was long overdue for an auteur of Campion’s stature, but the New Zealander is merely reaping the benefits of more than three decades of filmmaking of the highest order.

Campion has established herself as a much-needed voice in a decisively male-centric industry, and her meteoric rise remains one of cinema’s great success stories. Her unique sensibilities and narrative blueprint have earned her a place among the most distinguished female directors of all time as the recipient of the Palme d’Or, the Silver Lion and an Academy Award. Her case is also one of a fervid cinephile well-versed in the history of the seventh art who, as is the case with any worthy director, studied the masters of the past and learned from the very best of them. As we celebrate her latest contribution, we thought of assembling ten movies blessed with Jane Campion’s seal of approval. From underrated gems to timeless classics, let’s dive in.

1. Badlands (1973)

Kicking things off we turn to a director whose influence and narrative blueprint still reverberates in Jane Campion’s own work — Terrence Malick. Released at the height of the Vietnam War, Badlands retells the story of a runaway teenage couple who went on a killing spree and triggered a media frenzy back in the ’50s. The film not only established the debuting director as one of the most unique voices in all Hollywood, but also served as a poignant tale of disillusionment and loss of innocence that echoed the American psyche at the time.

During a recent interview, Campion cited it as one of the five films that she watched with her director of photography in prep for The Power of the Dog. “This is one of those rare creatures: a perfect film”. The director credits Malick’s film for giving her the confidence to find her own way to tell her western “strongly and beautifully”, praising the delicacy of his shooting style and observation. “Terrence [Malick] understands the poetry in every character, the couple’s brief time together in a kind of enchanted wasteland is unforgettable.” From the sweeping vistas of the American plains to the hazy narrative detachment, it would be an understatement to say that Campion’s latest hit owes a debt to Malick’s road classic.

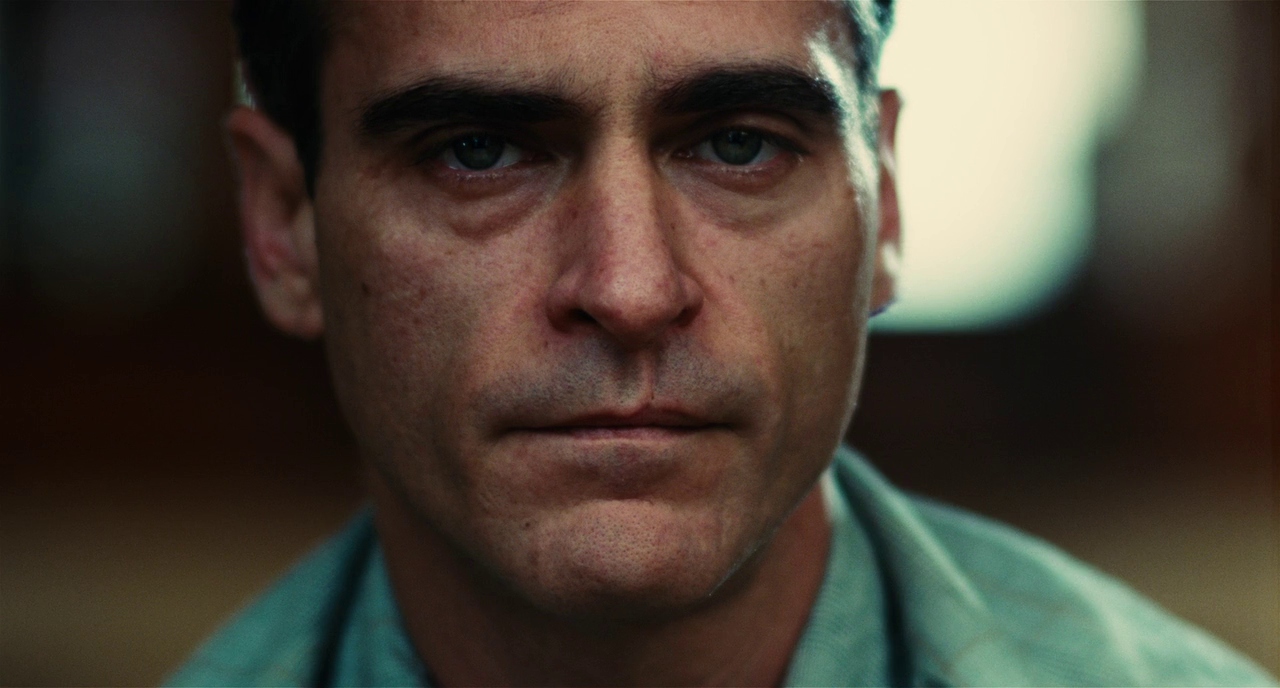

2. The Master (2012)

Paul Thomas Anderson’s incisive psychological drama puts us in the shoes of a shell-shocked World War II veteran (Joaquin Phoenix), who in one of his drunk escapades stumbles upon a charismatic cult leader (Philip Seymour Hoffman), loosely based on the founder of the real-life Church of Scientology. The Master is a portrait of obsession, ego and control essentially anchored by the fascinating power dynamic between these two clashing personalities; master and pupil, while condemning the way these types of organization wrap their tendrils around vulnerable targets only to exploit their emotional distress.

Campion cited PTA as one of her favorite filmmakers working today while crediting his work as a boundless source of inspiration. “I simply appreciate the texture of his world, the feeling of reality, and the photography of his characters that is qualitatively different, somehow more tender and curious than everyone else’s.” In regard to this film, she complimented how the story breaks away to tangential expressions instead of following tight casual patterns, thus discovering a “more elusive quality than straightforward closure”. “This may give a sense of poor completion, but positively, it overrides the narrative to keep the film open even as it is over.”

3. Tokyo Story (1953)

Jane Campion confessed that growing up, particularly during her formative years as an up-and-coming director, she felt a big disenchantment with films that were supposedly dominating cinema. “Major American movies just didn’t represent my life. I felt really alienated from the characters — everyone is so nice and they didn’t seem to have any problems.” This growing dissatisfaction further motivated the New Zealander to pursue her directorial aspirations and hopefully offer a fresh alternative to commercial cinema. Likewise, it forced her to seek inspiration elsewhere. “On the whole, I was more attracted to European cinema or people like Kurosawa than the world of Hollywood.”

The next entry in our list comes courtesy of Yasujirō Ozu, perhaps Japan’s greatest chronicler and a man who dedicated a significant swath of his career to deconstructing broader social realities through minimal domestic dramas. Tokyo Story follows an aging rural couple who pay a visit to their grown children in Tokyo only to be met with jaded indifference. As a bittersweet rumination on societal transformation, adulthood disillusionment and generational conflict, the film serves as a microcosm of Ozu’s entire oeuvre. Campion rightfully cited it among her favorite ten titles in the Criterion Collection. “I saw Tokyo Story for the first time recently. It’s an amazing film, delicate, beautiful, and full of a complicated wise love, utterly itself”.

4. Thelma & Louise (1991)

Campion’s oeuvre tends to orbit around headstrong women who rarely hesitate to subvert societal expectations placed on them in most cases by their oppressive, patriarchal milieu. This refusal to conform to their perceived roles drives forward many of the director’s films and often puts these unyielding heroines in perilous situations, whether it’s being dismissed as outcasts (Holy Smoke, Sweetie) or lost causes (An Angel at my Table, The Piano).

In that regard, Thelma Dickinson and Louise Sawyer both fall in line with Campion’s lengthy canon of resilient female leads. The two eponymous characters of Ridley Scott’s classic road film become fugitives upon fatally shooting a rapist at a roadhouse bar. This incident triggers a cross-country persecution throughout the Midwest that ultimately proves therapeutic for these two close friends, who not only find solace in each other’s company but savor freedom once again by essentially escaping the clutches of patriarchy.

During an interview, Campion went on to praise the ending sequence of the film, deeming it an empowering moment for the former housewife and waitress, who after a nerve-racking police chase through the desert, refuse to surrender to authorities and drive off the Grand Canyon in an iconic freeze frame that emphasizes their decision to control their own fate.

5. Days of Heaven (1978)

Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog is a slow-burn period piece that instead of adhering to a conventional narrative progression, rests almost entirely upon the thorny game of façades and bluffs between its characters. Critics have been quick to draw parallels between Campion’s latest hit and Terrence Malick’s contemplative classic, both thematically and visually. As is the case with most of his films, Days of Heaven is a sight to behold; as well as a poetic meditation on mankind, religion and industrialization that uses the early 20th century countryside as its idyllic setting.

Campion herself credited Malick’s second feature for helping her devise the right choices for her western, particularly in terms of the film’s atmosphere and the importance of nature in the story. “Days of Heaven is beautiful and elegiac; the amazing summer no one will ever forget.” The director went on to acknowledge the film’s sustained mood of romance and impending doom, especially when it comes to the central love triangle between Sam Shepard, Brooke Adams and Richard Gere. “There is the secret that cannot hold and the anxiety of wondering how it will fray”.