The “official” canon of classic cinema, compiled in lists such as the AFI Top 100 or the Sight and Sound polls, can be very useful for young cinephiles making their way through cinema history.For others with more experience, it’s still inherently fun to discuss these choices, to debate about the movies that make it and those that don’t.

And it’s in that aspect that these lists are often such a wasted opportunity, for they fail to go beyond the usual suspects; to look further and reclaim movies that have been unduly forgotten by time or even outright dismissed for no good reason. Female and non-white filmmakers particularly have had their immense contributions overlooked, something that critics are, fortunately, starting to remedy, rediscovering some lost classics and giving these pictures their rightful place in the sun.

With that in mind, here’s a list of 10 excellent movies directed by women that you may not have seen but definitely should, as soon as possible.

10. The Hitch-hiker (1953)

Ida Lupino’s place in the canon of Hollywood cinema was for a long time obscure, relegating the pioneer filmmaker to the peripheries of history, denying her the same acclaim bestowed on many of her male contemporaries.

Recently, however, film historians and critics have looked upon her movies and place in the industry with a keener eye, recognizing both the trailblazing nature of her work (by virtue of having been made by a woman in the 40s at all) and the artistic merit of the pictures themselves.

It’s difficult to single out a particular movie in her filmography, which is filled with undiscovered gems, but “The Hitch-Hiker” seems a perfect starting point for newcomers to her work, since it works on so many levels; just as compelling as a pure, unpretentious genre picture (as tense, tight and to the point as the best of classic noirs) and as a symbolic exploration of male violence, represented through the phallic figure of the gun.

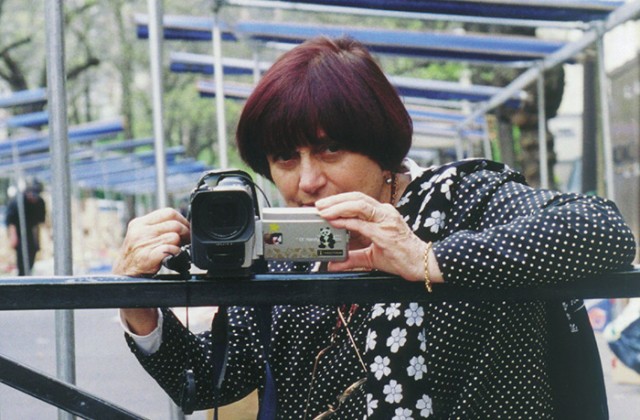

9. The Gleaners and I (2000)

Agnes Varda’s legacy is a paradox; she is simultaneously recognized as a cinematic titan, one of the all time greats (just as essential a figure of the Nouvelle Vague as Godard, Truffaut or Chabrol); but still remains somewhat underrated, in the sense that so many of her movies continue to be largely underseen.

After all, bar some superlative classics like “Cleo From 5 to 7,” Varda’s oeuvre was for a long time obscure, even to many critics; whether due to lack of proper distribution (trapped in the rarefied circles of festival screenings, with little to no presence in physical media and streaming) or by dint of having been dismissed upon release and never reevaluated or reclaimed. Thankfully, in the last few years venues like Criterion have restored and made available many of her films, allowing for more people to discover their brilliance.

And while Varda made many wonderful pictures throughout the entirety of her career, her late non-fiction work merits particular attention; unlike so many other directors who peter out with age, Varda kept putting out masterpieces to the very end. Her documentaries, such as “The Gleaners and I,” are a miracle, achieving an almost impossible balance: they are both formally ambitious, intellectually rigorous work and light, life affirming entertainment.

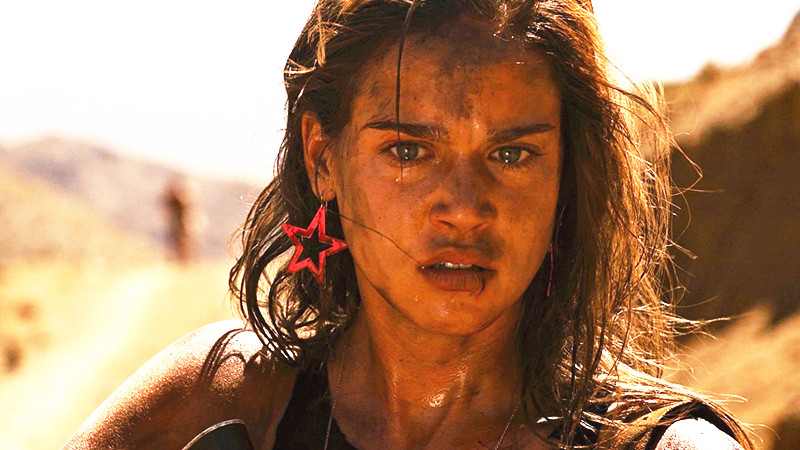

8. Revenge (2017)

Rape revenge movies are not an inherently misogynistic subgenre; in fact, if anything, they’re uniquely suited for being cathartic expressions of righteous female rage. That potential, however, has rarely been fully tapped into, because the genre has been predominantly dominated by male directors, who are often more interested in the lewder aspects of these stories.

Coralie Fargeat’s phenomenal “Revenge” is the best possible version of a modern exploitation film; a thorough rebuttal of this history of objectification, but also a genuinely incredible piece of pulp nastiness. An unfortunate trend of modern genre cinema is the proliferation of “elevated” pictures, that is, movies that seek to modernize or complicate genre tropes but, in the process, believe themselves to be superior to older classics.

Fargeat is far too intelligent a filmmaker to fall for such cheap faux-arthouse smugness; her “Revenge” works incredibly as pure exploitation, with maniacally violent and well-constructed set pieces (the budget for fake blood on this film must have been a fortune), while simultaneously offering pointed, intelligent gender critique. It’s a film that proves you can truly have it all.

7. A New Leaf (1971)

It’s fair to say that at this point Elaine May has been fully reevaluated as a major filmmaker; a key figure of the New Hollywood, both artistically and historically, considering she has become in the public consciousness an avatar for the double-standard for female directors, a living embodiment of the lack of opportunities women have to face in the industry.

May only ever directed four features but, in a fair world, she should’ve had as varied, long and fruitful a trajectory behind the camera as her old improv partner Mike Nichols; she was every bit as talented as him, if not more – after all, aside from being a director, she was also a terrific writer and actor. One needn’t look further than her debut, “A New Leaf,” to witness what an immediately brilliant filmmaker she was from the get go.

A screwball comedy that is equally as acidic as it is sweet; the film is of one cinema’s finest farces, taking the archetypes of classic screwball and exaggerating them to absurd proportions – this is a love story between a nihilistic sociopath and the impossibly naive heiress he plans to murder, which in anybody else’s hands could’ve been disastrous, but May makes relentlessly hilarious and, somehow, genuine romantic. A magic trick.

6. Ishtar (1987)

As said, May’s reputation has been almost completely restored; critics who initially dismissed her have either vanished or retracted, and a new generation of cinephiles have embraced her short but rich filmography – or at least most of it.

There’s one movie whose failure was so loud and notorious that not even decades of a changing critical landscape has been enough to fully rehabilitate it’s poisonous fame: “Ishtar,” the film that virtually annihilated May’s directing career in a single fell swoop. It had one of the most catastrophic productions of any Hollywood film ever (on par with “Heaven’s Gate” and “Apocalypse Now” in terms of succeeding disasters). The picture went wildly over-budget, was hindered by constant in-fighting between May and her collaborators (particularly Warren Beatty and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro), and even had a chaotic post-production with three editors working on different cuts simultaneously.

Stories of it’s troubled production began to spread even before the film’s release, becoming the dominating narrative around the movie for months and creating an atmosphere of hostility and bad faith – making it’s overwhelmingly negative reception, both critically and commercially, a foregone conclusion.

Looking back, however, it’s possible to discern that all the backstage drama outgrew the actual movie, which is a flawed but intermittently brilliant farce; every bit as deliriously witty as any of May’s celebrated screenplays and visually lavish in a way comedies can rarely afford to be.