Since the genesis of cinema, the crime genre has unfalteringly persisted as a firm favourite among audiences worldwide. Although the ‘40s or the ‘90s are often referenced as great times for noir and neo-noir cinema, respectively, the 2010s boasts its own hefty share of crime classics.

Most movie fans are already familiar with well-publicised triumphs like The Irishman. However, a myriad of excellent crime movies from the past decade remain puzzlingly overlooked or shrugged-off. They easily match or surpass the quality of the best-rated titles in the genre. They’re in-need of much-deserved reappraisal.

1. El Infierno (Luis Estrada, 2010)

“I’m only doing this because I have no choice.”

The title translates to: ‘Hell,’ in English. One of the best Mexican films ever made, this monumental Spanish language narco pelicula concerns Benny (Damián Alcázar), who emigrated from Mexico to the United States as a young man. 20 years later, he’s deported to a homeland he no-longer recognises, stricken by the War on Drugs. With money as dry as the San Luis Potosí desert, in spite of his hatred of them, Benny’s enticed into working for the cartel. In the company of Ernesto Gomez Cruz and telenovela actress Elizabeth Cervantes, Narcos: Mexico’s Joaquín Cosio plays flamboyant drug baron: ‘Cochiloco.’

In perhaps the most resonant, meaningful, nation-defining crime film ever made, Estrada’s cautionary tale shows us how Mexican people continue to endure of the bloodshed of the deeply-entrenched cartel, especially in the northern desert states. In an economic landscape decimated by the 2008 Financial Crisis, El Infierno shows audiences the cartel’s enslavement of the police, religion institutions and government, the indoctrination of children into a life of murder. It is a denouncement, an exposé of a deeply-damaging issue in Mexican society, pointing a finger at those whom have struck terror into the lives of the Mexican people. What is more, El Infierno examines the United States involvement of drug importation and how that effects Mexico’s power balance. The racial tensions between indigenous and colonial-descended Mexicans are also considered.

More broadly, with Benny as the audience’s eyes, El Infierno details how an ordinary, kind-hearted person can be mutated into a murderer, the dichotomy between money or morality. With a fast-moving pace, the story’s progression is determined by the characters, not a contrived structural imposition, adding to its verisimilitude. There’s also gallows humour present, over the slide guitar and Czech-tinged Tejano accordion soundtrack. Whilst being incredibly moving, El Infierno delivers on all genre fronts for a perfect, fresh-feeling crime movie, boasting atmospheric production design and masterful performances across the board. Easily one of the best films of the 2010s and a must-watch.

2. The Outrage Trilogy (Takeshi Kitano, 2010, 2012, 2017)

Comedian turned mob chronicler ‘Beat’ Takeshi Kitano wrote, directed and acted in: Outrage (2010), Beyond Outrage (2012) and Outrage Coda (2017). His epic saga journals the bitter in-fighting between rival yakuza clans in Japan’s Kanto region. Japanese acting giants Jun Kunimura (Kill Bill) and Toshiyuki Nishida co-star alongside adept newcomer Tokio Kaneda.

In Japanese aesthetics, there exists the concept of Yūgen. Inexpressible through words, it means “the subtle profundity of things that are only vaguely suggested by poems. That which is beyond what can be said.” Yūgen is a prominent quality in Japanese arts, especially in haiku, but also in Noh theatre and ukiyo-e woodblock prints. The Outrage Trilogy, like Kitano’s Sonatine, is brimming with the delicate, transcendent beauty of Yūgen. Katsumi Yanagishima’s graceful cinematography exudes an inexplicable atmosphere of Zen, stillness, poeticism – a silent meditation on life and death. Likewise, this trait was ever-present in the filmography of Kitano’s idol: Jean-Pierre Melville, who engendered an indelibly Buddhistic tone around his sparse dialogue.

Growing-up, Kitano spent time around the yakuza and claimed he might’ve joined them if he hadn’t become a standup. His intimate knowledge of the yakuza is apparent in everything from the specificity of their Irezumi (full-body tattoos) to the conduct of their sake-drinking pact. The violence in Kitano’s films may be the only cinematic depictions that feel authentic. Murders are swift and life-changing. “I intentionally shoot violence to make the audience feel real pain,” asserts Kitano. “That’s how it is in real life and that’s how it should be expressed. I have never and I will never shoot violence as if it’s some kind of action video game.” By letting the camera linger on a corpse in the road, Kitano aids his audience’s understanding what violence truly means.

Despite making the trilogy “with no other ambition than to be entertaining,” Kitano achieves much more than this remit. It also professes much of his finest dark humour. When a character asks Otomo (Kitano) what his name is, in typical fashion, Otomo snaps: “My name is f*ck off.” The Alain Delon-esque, poker-faced antihero Kitano has cultivated in his work (starting with Violent Cop) is at-once hilarious, menacing, mysterious and philosophical: an unsettling chameleon of entertainment. For crime fans, The Outrage Trilogy quenches a thirst, ticking all the right boxes. It’s only matched by Goodfellas in its ambitious scope, entertainment value and flawless delivery.

3. The Guard (John Michael McDonagh, 2011)

In John Michael McDonagh’s raucous directorial debut, FBI Agent Wendell Everett (Don Cheadle) is dispatched to Connemara, on Ireland’s rural west coast. He’s to lead an investigation into drug trafficking. The only thing he wasn’t prepared for was being partnered with irreverent, law-ignoring local cop: Sergeant Gerry Boyle (Brendan Gleeson). This ‘Irish western ’remains the most financially-successful independent Irish film of all-time. Criminally underrated, it’s inarguably one of the best directorial debuts.

The Guard’s cleverly-written, laugh-a-minute detective and gangster fun foreshadows McDonagh’s equally-brilliant subsequent work. Confidently brought to life by Gleeson and Cheadle, McDonagh writes interesting and colourful dialogue filled with allusions to philosophy, in this case Friedrich Nietzsche. It’s joyous to see Cheadle to return to comedy. It’s genre he’s highly-proficient at but does not usually get the opportunity to enhance, other than as country music-loving Buck in Boogie Nights.

The Guard’s especially aesthetically beautiful in the context of British and Irish cinema, with its Almodóvar primary colours, green lighting and painterly framing. One technique of note is when the camera is fixed upon a tripod on a beach, filming the Atlantic at nighttime. Without moving the frame, it cuts to the same shot, but in daylight, making for a fresh and exciting editing transition. The film’s spaghetti western bravado is supported by Calexico’s flamenco soundtrack.

One of the things this film achieves is finding humour in controversial areas. When Boyle makes racist remarks to Wendell Everett, it’s understood that he’s not doing this to upset Wendell or because he’s a genuine racist. “I’m only havin’ a bit of fun, like.” This is Boyle’s eccentric way of making friends with Wendell: saying politically-incorrect jokes to break the ice, hoping they can share a laugh together. Boyle finds people’s reactions to his outrageous jokes hilarious. His unusual, cheeky sense of humour ultimately nurtures a camaraderie between the two lawmen. Though this is best evaluated by African American viewers, through McDonagh’s writing, it’s apparent The Guard’s intention is to be funny and satirical, not to declare a racist philosophy or mock African American people. If the latter was its true resolve, it probably wouldn’t’ve been released cinematically and certainly wouldn’t holdup as one of the funniest comedies of the 2010s.

4. Spring Breakers (Harmony Korine, 2012)

School friends Faith (Selena Gomez), Candy (Vanessa Hudgens), Brit (Ashley Benson) and Cotty (Rachel Korine) run away from their dull hometown to experience spring break in St. Petersburg, Florida. After being rallied by seedy gangster rapper ‘Alien’ (James Franco), the young women become embroiled in a life of crime.

Spring Breakers is to the 2010s what Easy Rider is to the 1960s: a decade-defining piece. Upon its release, some audience members couldn’t decipher whether it was a tribute to or “an indictment of vapid youth culture.” Korine gives his viewer the space to makeup their own mind on the excesses of that era. Establishing the ‘Florida pink noir’ sensibility he’d go on to accentuate in The Beach Bum, in Spring Breakers, Korine invents an entirely new mode of cinema. It’s a dreamlike “collage,” wherein narrative is secondary to feeling, experience and atmosphere. “Micro-scenes which were then looped,” Korine elucidated. It’s a film unlike any other.

On his creative choices, Korine explained: “The movie was more meant to mimic a drug experience, a ride or a physical experience. Maybe it’s more musical or experiential than it is a traditional narrative. Based on a pop song, with hooks – a catchiness to it. More kind of a game. I [wanted it] to look like it was lit with skittles. I loved the idea of working with those girls specifically because, in real life, [they’re] representative of that culture, of that dream.”

Although it was subsequently included in the BBC’s ‘100 Greatest Films of the 21st Century,’ Spring Breakers remains a chiefly misunderstood work of groundbreaking genius. Whatever trash one expects from its poster or trailer is immediately dispelled by its poeticism, social significance and empyrean beauty. Korine’s filmmaking advice is: “give me something amazing. Give me something new. Give me something I haven’t seen before, in a way I haven’t seen it. Make me feel something. But just don’t give me the same sh*t over and over again because I don’t want it.”

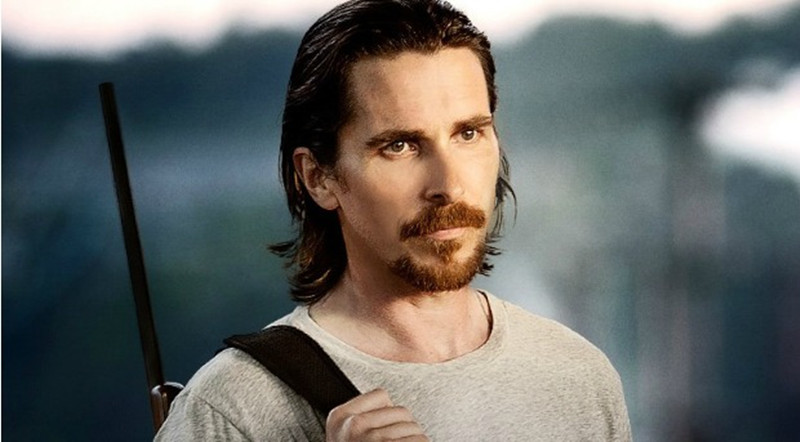

5. Out of the Furnace (Scott Cooper, 2013)

In the rust belt of Pennsylvania’s Appalachian Mountains, mill worker Russell Baze (Christian Bale) helps his younger brother Rodney (Casey Affleck), a boxer, with his debt to infamous hillbilly godfather Harlan deGroat (Woody Harrelson). When Rodney goes missing, Russel ventures into the backwoods to find him, assisted by his friend John Petty (Willem Dafoe).

Out of the Furnace is the second film of Virginian director Scott Cooper, following his 2009 debut Crazy Heart. A realistic drama first and a noir second, it examines the American dream and the Financial Crisis’s life-changing consequences for working class Americans. It also achieves a portrait of how wartime traumas continue to emotionally harm veterans. Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder makes contributions to its haunting soundtrack.

Out of the Furnace contains arguably the best scene in 2010s cinema. This takes place on a bridge and depicts the reunion between estranged lovers Lena (Zoe Saldaña) and Russell (Bale). Monumental, timeless truths are revealed within this scene. Of it, Bale reflected: “I realised, during it, this is a man seeing all of his dreams and hopes for his life completely obliterated.” It’s dramatic writing at its relatable, heart-wrenching best.

In addition to Bale and Saldaña’s exemplary performances, Woody Harrelson is nastier and more frightening than in any other role, elevating Harlan deGroat to the ultimate villain. Moreover, Forrest Whittaker and Dafoe are typically exceptional, as is the late Sam Shepard – making an art form out of the understated. While delivering all the style and action one desires from a great crime movie, Out of the Furnace has distinctly literary concerns. A film of this standard is ineligible for the lukewarm response it bewilderingly received upon its 2013 release.