Horror is a genre that wears many different faces, much like the monsters that populate them. There’s something in them for everybody, whether you’re searching for a sheer rush of adrenaline or something more substantial and intellectually intoxicating. For every fun, boilerplate slasher in which a group of attractive, sexually promiscuous, weed-obsessed head out into the woods only to find themselves hunted and being picked off one by one by some deranged psychopath in a hockey mask, there is a more cerebral and emotionally involving narrative centered around real-world issues and human-based anxieties, whether it be coping with grief, figuring out one’s place in the world, or struggling to be a single mother. The beauty of horror is that the possibilities are endless. Like ice cream, there are a variety of flavors from which to choose.

From the beginning of horror’s genesis, countless filmmakers have capitalized on the zeitgeist of their respective time periods to tell stories that resonated with their audiences. A general rule for this particular art form is that if people are able to relate to the horrors being inflicted on their on-screen surrogates, the horror will hit that much harder, because it’s hitting a place where we live. We see ourselves, and in some cases, feel as though we are confronting these fears head-on right alongside the characters.

In the list below, we will be taking a look at ten of the most socially relevant entries in the horror genre, and for some, you may find yourselves examining certain films from an entirely different – and unsettlingly topical – lens.

1. Night of the Living Dead (1968)

Zombies are all the rage nowadays, or so it seems. Everywhere you look on TV, there seems to be yet another movie or TV series revolving around a post-apocalyptic outbreak that has given rise to an invasion of flesh-eating, mindless monsters with dead-eyed expressions and an insatiable appetite. Edgar Wright is one of the earliest and most successful filmmakers to satirize this long-exhausted subgenre with his classic 2004 horror spoof, Shaun of the Dead, in which Wright used his hordes of zombies to pose an amusing question: We live in such a lifeless, desensitized world now; if suddenly we woke up one morning and our neighborhoods were being taken over by brain-dead, groaning monsters, would anyone even notice?

However, before zombies became a running gag to poke fun at our consumerist culture and provide gallons upon gallons of tongue-in-cheek gore, there was one man who wanted his “ghouls”, as he referred to them, to be taken 100% seriously. In 2023, that may sound like a chortle-inducing proposition, but in 1968, at the height of Cold War-era tensions between the U.S. and Soviet Union, it racked up hundreds of morbidly curious filmgoers in the theater, and the general reaction was far from a contemptuous snicker.

Early one morning, two young adult siblings, Johnny and Barbara, make a trip to a deserted cemetery to visit the gravesite of their grandfather. There, a strange old man – disoriented, stumbling around like a drunk, dressed in black – wanders up to the siblings and inexplicably begins attacking Barbara. After Johnny is killed trying to defend his sister, Barbara races to a mysterious house to seek shelter and safety. As day turns to night, a group of survivors must band together and set aside their differences to figure out how to defeat this rapidly growing horde and save themselves from becoming pieces of meat to be chewed on.

The character who seizes control of the situation is a level-headed, proactive black man named Ben who seems to know exactly what to do to keep everyone safe and keep the ghouls from getting inside. But in the end, nothing matters – everyone in the house is killed and the last survivor, Ben, is shot dead by, of all people, a Caucasian police officer, who mistakenly assumes Ben is just another ghoul to be executed. If that isn’t a fairly blatant metaphor for the state of racism and police brutality/indifference that we are still hearing about on the news 54 years later, what is? And as for the ghouls feasting on the flesh of their victims, where can you find a greater allegory for our materialistic society than that? After all, there isn’t much more you can consume beyond the literal bodies and blood of your fellow human beings.

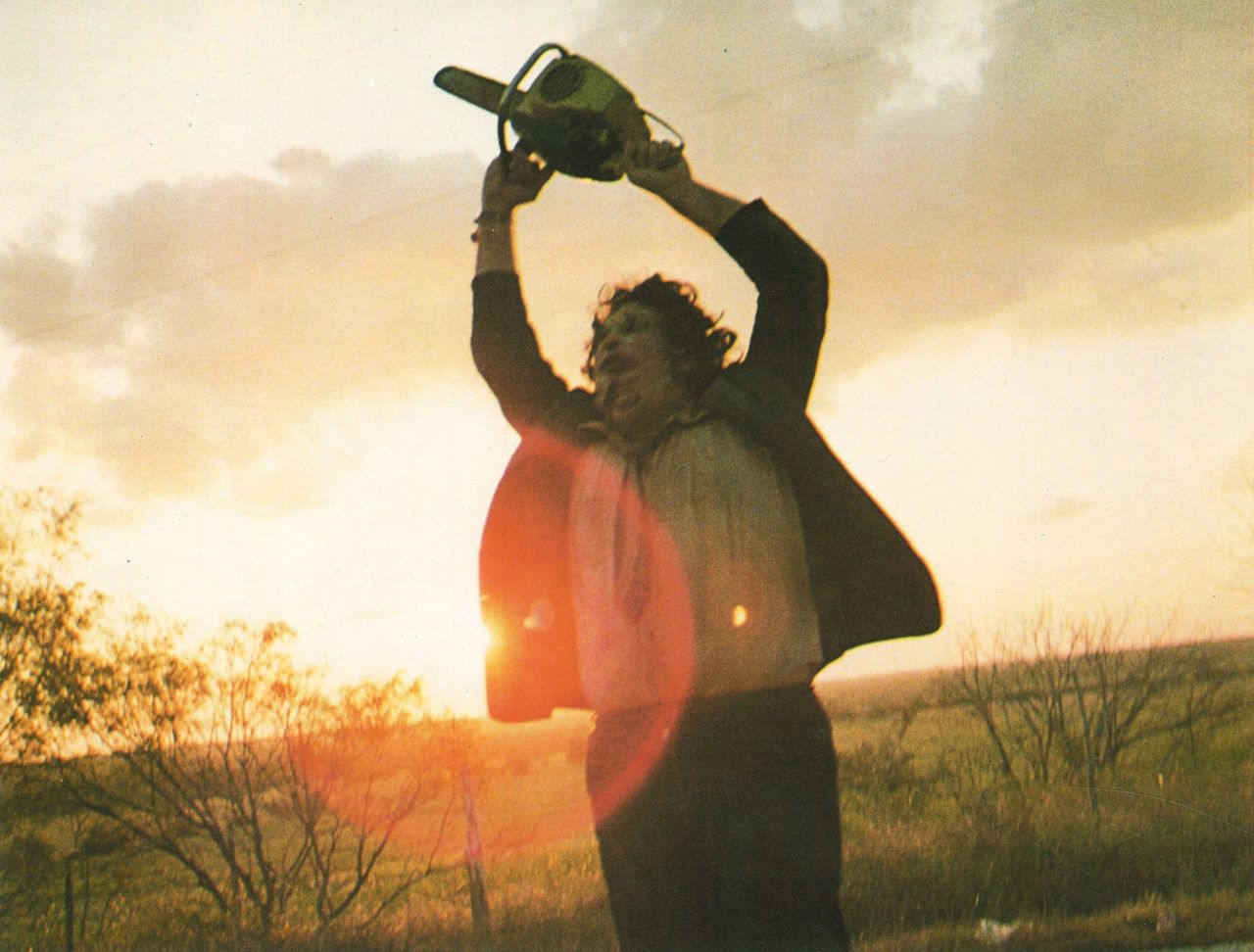

2. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

The early 1970s was a time of serious upheaval. Conservative family values were being subverted by the emergence of the hippie counterculture, the sexual revolution created by disillusioned youths craving to get more fun out of life than what was expected of them, and the image of the nuclear family unit was gradually deteriorating into a grotesque parody of its former self, symbolized by the inbred, cannibalistic Sawyer family at the center of Tobe Hooper and Kim Henkel’s groundbreaking 1974 teen slasher masterpiece, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Similar to the setup of the first entry on this list, Texas Chainsaw follows a day in the life of Sally Hardesty and her invalid brother, Franklin, who travel by van one Saturday afternoon to visit the gravesite of their grandfather after hearing about a series of grave robbings in the area. They are joined by three of their friends, all of whom have no way of suspecting the nightmare they’re driving straight into as they unwittingly cross paths with a large, deformed serial killer who wields a chainsaw and wears the faces of his former victims. By the following morning, only one of these young adults will have escaped with their lives, if not their sanity, intact.

While first and foremost one of the scariest and most shocking horror films ever made – banned in several countries and condemned by the church, no less – Texas Chainsaw is also notable for its pro-vegetarian stance as it openly discusses the callousness and evil of slaughtering animals for food. Say what you will about the Sawyers, but they do not eat poor, defenseless animals when they’ve got a lineup of carefree youths in their sight.

3. Candyman (1992)

Instead of our usual boogeyman, who serves as a personification of pure evil and kills merely for the pleasure of it all, Candyman makes the daring move of turning its ultimate victim into a malicious specter hellbent on causing the same pain to others that was inflicted on him. Tony Todd stars as the titular phantom, the free son of a slave who was chased, cornered, and brutally lynched by an angry mob simply for being a black man who “dared” to fall in love with and impregnate the white daughter of his employer. Now his soul haunts the residents of a disenfranchised apartment building in Cabrini Green, appearing in a mirror once his nickname is spoken five times and eviscerating those who denied his existence with the hook that was jammed into the bloody stump of his sawed-off hand.

The social commentary on racial injustice is not subtle – at one point, Virginia Madsen’s protagonist, Helen Lyle, comments aloud to her friend, “Two people get brutally murdered and the cops do nothing. Whereas a white woman goes in there and gets attacked, and they lock the place down” — but it’s no less hard-hitting and incisive for it. For once, there’s more going on in a slasher film than gory kills (though there are plenty) and T&A. This is an adult slasher story for those that love to be thrilled both viscerally as well as intellectually.

4. The Entity (1982)

Being a woman already comes pre-packaged with its share of burdens in the world. Imagine being a widowed single mother raising three kids on a low income while going to school and being molested and beaten regularly within an inch of your life by three indiscernible demons who can come in and out of your own home at will. That’s the predicament Carla Moran finds herself in.

We are now living in the #MeToo era, where more and more women are stepping up to speak out against the men who have damaged and silenced them for far too long. Many have received a degree of justice, with real-life powerful men like Harvey Weinstein being thrown behind bars for the remainder of their days. Unfortunately, there will always be more men who get away with it, and more women who will simply have to suffer. Carla is one such woman.

After being referred to a psychiatrist, Carla’s claims of being raped by three ghostly invaders fall upon deaf ears, Dr. Sneiderman trying earnestly to convince her that these are merely delusions brought on by her repressed memories of sexual abuse by her father from childhood. No matter how loudly Carla screams, no matter how certain she is that these are not delusions, nobody will believe her unless they’ve witnessed the paranormal abuse for themselves.

In the end, Carla moves away to a new city, but the entity is not vanquished. It will follow her and her family no matter where they relocate. She will suffer, endure, and survive. And today, that is the strongest and most authentic allegory for the state of being a woman in a man’s world.

5. The Babadook (2014)

Amelia Vanek is a single mother and widow raising a wild, capricious 7-year-old son named Samuel, whose birth inadvertently led to the sudden and violent death of her husband. Samuel has an extremely active and vivid imagination – at least Amelia thinks that’s all it is – which leads him to believe a monster from a mysterious storybook named Mister Babadook has materialized and is now targeting Sam and his mom in their decrepit, shadow-heavy home.

More than a mere monster movie or exploration of children’s fears of seeing monsters and not being believed by their parents, this psychologically penetrating, achingly heartfelt, devilishly intelligent horror drama confronts a terror more horrifying than any storybook monster lurking in the shadows could be: the fear of failing as a parent. Amelia is stressed beyond words and suffering from repressed depression and isolation. She refuses to utter her late husband’s name and has absolutely no friends to turn to. Even her sister stops coming by because she “can’t stand being around [Amelia’s] son!”

In a cacophonous, emotionally charged dénouement, Amelia stands up to the monster plaguing her and Samuel, refusing to be defined by her grief any longer, and making a decision to live with it. As for the Babadook himself, with his clawed fingers, pasty face, and black cloak, he is a living embodiment of grief and depression, and the only way to defeat him (or at least gain the upper hand) is to stare him straight in the face and say, “You are nothing!” Like the feeling of grief itself, it can never die. It just hides downstairs in the dark, musty basement of our own subconscious.