“Everything is blooming most recklessly; if it were voices instead of colors, there would be an unbelievable shrieking into the heart of the night.”The poet Rainer Maria Rilke, long known as a voice of the most ineffable of human solitudes and longing, has much to offer in ways of understanding the work of Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-wai. Rilke, a significant character in prefiguring modernism, sang the insufficiency of the human condition, man’s tendency to find himself alone despite the abundance of beauty in life and all of its possibility.

Film director Wong Kar-wai captures this same essence of individuals’ alienations from each other, and the resulting emotional – and volatile – anxiety. Wong, too, is a poet; his character’s inner lives bloom recklessly under the florescent lights of Hong Kong nights and behind doors in rooms of modern isolation. Rather than cry out, they retreat inward. Wong Kar-wai’s films thusly contemplate the human condition in all of its eternal and contemporary implications.

These entries exemplify the director’s preoccupation with probing the most intangible of human desires.

1. As Tears Go By (1989)

This feature-length directorial debut establishes many of what would become Wong Kar-wai’s trademarks, both thematically and aesthetically. The film marks the first collaboration between the director and Hong Kong actress Maggie Cheung. As Tears Go By tells the story of a young Hong Kong underground up-and-comer who is torn between loyalty and love. The disturbance of his shy cousin appearing in his life sparks the conflict between past and present.

Until this moment the protagonist’s life is unchanging, unexamined. His cousin becomes the object of his longing, representative of a future he had never before considered. As the protagonist is drawn toward this newly realized future, he is inevitably pulled back by his violent past; gang loyalties and a sense of responsibility force him to depart from his idyllic future back to the Hong Kong underground.

The geographical and temporal displacement of Wong’s characters are significant features of his cinema: characters frequently travel back and forth between places on the simplest of whims. However, these efforts to confront their spatial and temporal separations are often in vain. Even when the protagonist realizes his potential for happiness, his link to the past perpetually anchors him in the present, unable to move on. The character’s awareness of this connection is what decidedly seals his fate.

Wong Kar-wai’s aesthetic predilections are apparent from this debut. In the opening scene, the main character is woken by his aunt calling, and she tells him that she’ll call back later. However, only two cuts and seven seconds separate the now from later; with little changing aesthetically this is a jarring non-representation of time. This is director Wong Kar-wai preparing the audience for the tenuity of chronology in this film, and in his work to come.

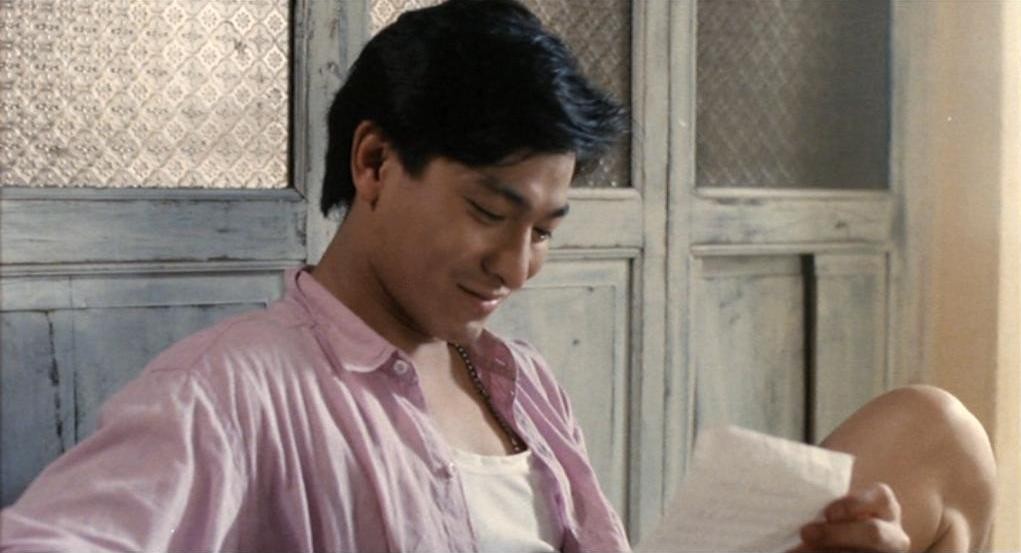

At the end of the first act the protagonist’s emptiness and longing are realized in a moment which uses a trademark Wong Kar-wai device, voiceover. In this case, it is the cousin who has now departed for home reading the letter she has written to her cousin. Images of the main character reading the letter are cross-cut with images of his empty apartment, his cousin traveling home, and the landscape. This is a frequent device of Wong’s to convey the poetics and mechanical processes of memory, nostalgia, and self-reflection.

Wong’s conceptions of time transcend narrative into the actual means of production, such as his manipulation of film speed. In a process which Wong would later perfect with cinematographer and frequent collaborator Christopher Doyle, the images are shot at a low frame rate and then step-processed at an even slower rate onto the finished film stock to restore the action to its real time length.

The resulting images are confounding, neither slow- nor fast-motion, but something altogether separate from real-time. They are distorted, jerking forward, blurring lights and colors across frames. Not to be confused with the ethereal, these images are dreamlike in a more jarring way. In As Tears Go By, Wong uses this technique to create a internalized depiction of violence and vengeance. It is an ultra-personal scene which reveals the depths of the main character’s loyalty. The process is used again at the end of the film in a similarly poetic way, as if to comment on the inevitably of the main character’s fate.

As Tears Go By is Wong Kar-wai’s first and most straightforward feature-length film. Despite its linearity and narrative cohesion, it is only the jumping-off point for his explorations of time, place, love, and longing.

2. Days of Being Wild (1990)

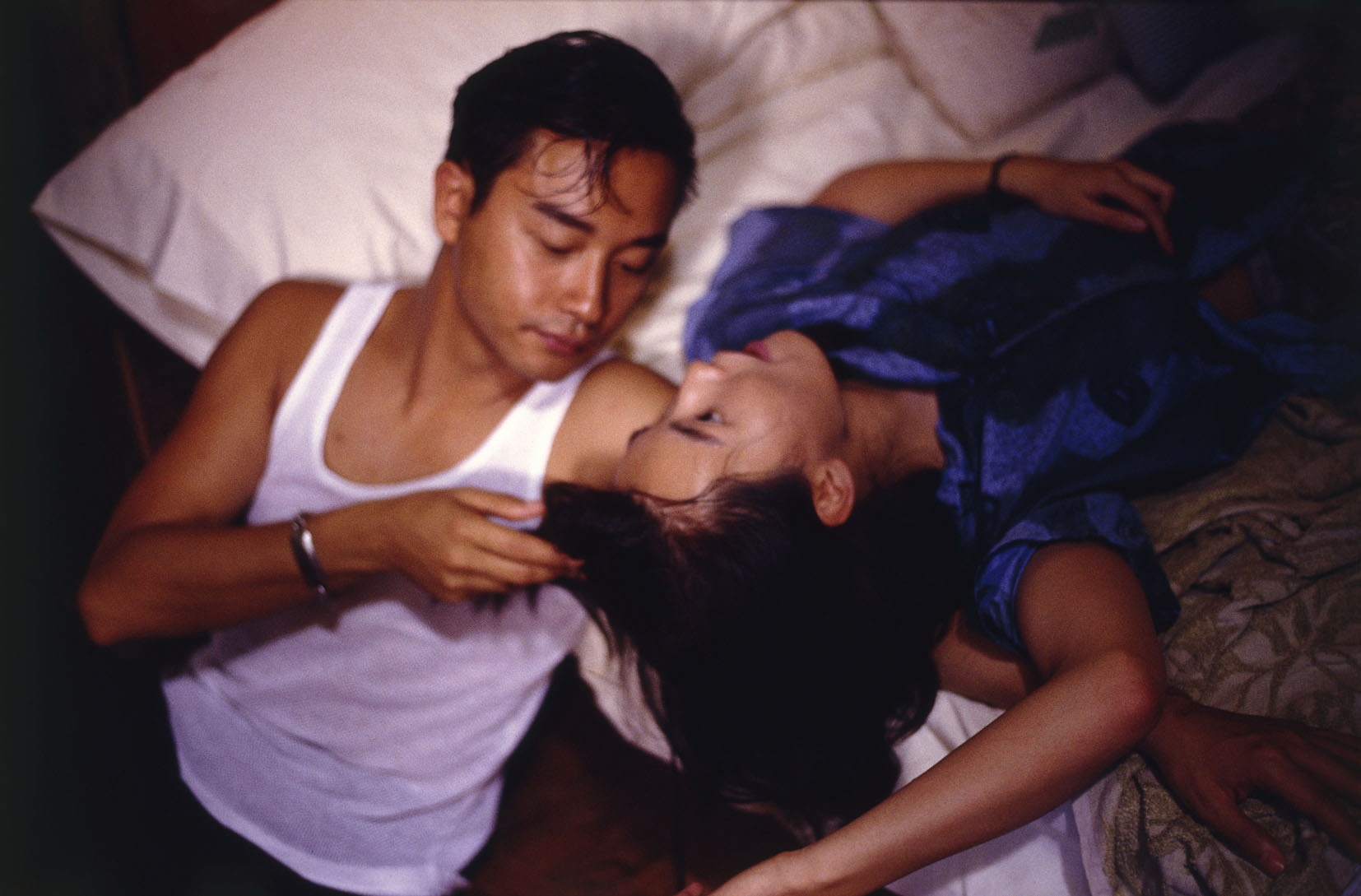

If Wong Kar-wai’s feature-length debut presented the themes he would go on to explore with an almost-obsessive rigor, then his second film established him as an authentic voice in the unfathomable landscapes of human suffering. Set in a poignantly rendered 1960s Hong Kong, Days of Being Wild, as the title suggests, is about the search for intimate connection, a quest for a sense of identity and purpose, and the consequences of reckless love.

The film popularized a genre of Hong Kong films known for its art-house aesthetic, relying on the ability of actors to sustain the emotional arcs of their characters through the mundane aspects of daily life rather than a strict adherence to plot. The film marks the first collaboration between Wong Kar-wai and cinematographer Christopher Doyle, and examples such trademarks as heavily saturated and mixed lighting sources, the manipulation of film speed, and images otherwise distorted via focal length, filtration, camera movement, etc.

The three main cast from Wong’s debut return: Maggie Cheung stars as Su Li Zhen, a young snack shop worker jilted by a handsome heartbreaker, while Jacky Cheung resumes his role as an emotionally-charged sidekick, and Tears star Andy Lau takes up the quiet role of a lonely night patrolman. Aside from working with the best actors and actresses of Hong Kong cinema, Wong’s casting also serve a thematic purpose.

Past collaborators return in similar – sometimes nearly-identical – roles, a commentary on the nature of identity and memory. His characters, removed from all temporal and geographical context, are perpetually longing, always searching for fulfillment and purpose. Days of Being Wild also constitutes the first entry into a thinly-veiled trilogy continued ten years later in In the Mood for Love (2000) and still further in 2046 (2004) – to say that Wong Kar-wai ever concludes this story would be athematic.

Days of Being Wild offers none of the however-slight conclusion at the end of Tears. It is Wong’s first decided step in the restless journey for self-discovery and permanence. A handful of characters are presented in their daily lives, seen alone at work or home, colored by their private thoughts and feelings about time, being, and belonging. The heart of the film is how people deal with rejection: the women are discarded by the same man and in the same manner, but deal with their pain in different ways.

The man himself deals with an even more private conflict, inconsistent feelings about his former-prostitute adoptive mother, and the absence of his biological mother, a Filipino aristocrat. The film crosses borders in both time and space, portraying the inner as well as literal journeys of the characters. In this way equal weight and emotional depth is given to the jilted lovers, the womanizer, his candid and self-effacing sidekick, and a solitary policeman.

In Days of Being Wild, Wong introduces his evocative disruptions of plot, wherein an presumably minor character is shifted to the foreground. Here, this is accomplished through voice-over; the night patrolman, his romantic love having never materialized, leaves Hong Kong to realize his dream of becoming a sailor abroad.

However, this departure remains within Wong’s realm of unremitting longing: the former-policeman now-sailor meets the young philanderer in the Philippines, on his own unfulfilled search for his biological mother. This is the beginning of Wong’s contemplation on chance, fate, and free will, which will remain at the center of his subsequent works.

Here, all love is unrealized and insignificant. Each of the rejected women are sought by other men on the periphery, whom they either use, ignore, or otherwise fail to accept in turn. Plot-wise, little happens as these characters haphazardly navigate their daily lives and spend their time in wait, unaware that opportunity has passed them by.

They are all victims of time, change, and issues of identity and belonging in Wong Kar-wai’s 1960s Hong Kong. However, in the final scene, there is the suggestion of an enduring human spirit. At once troublesome and evocative, the end of the film sees the minor character played by Tony Leung – who will star in In the Mood for Love and 2046 – getting ready for a night on the town, and departing his cramped room.

After testing the waters with Tears, Days of Being Wild jumps on in to the boundless oceans of inexpressible sufferings. In his second film, Wong eschews plot and fully follows the emotional whims of his characters with utmost faith in their integrity. Wong’s approach is nonjudgemental, as there is no good and bad in the longing for intimacy and connection, self-knowledge and substance. There is only individual’s journey, and the unfortunate consequences as we recklessly grasp at fulfillment.

3. Ashes of Time (1994)

Ashes of Time presents as Wong Kar-wai’s perhaps most challenging film to date. It lacks the context and specificity of the Hong Kong settings in his other films, where any outside travel serves as a punctuation in the narrative. Instead, Ashes tells the story of an agent by the name of Ouyang Feng, and the several bounty hunters he hires. The film is technically an adaptation of the novel The Legend of the Condor Heroes by Jin Yong. However, Wong only uses the novel to loosely base his film on four of the characters, throwing out all plot adaptation. The result is a film that, despite its departures, is very much of the director’s spirit.

Ashes is a mood piece of a film. The story spans years, however, the characters are never removed from the deserts of Ancient China and there are no other indicators of chronology. The desert is an entrapment for all of the characters – a place of uncompromising necessity and self-sufficiency. Human beings are reduced to the most primal modes of survival.

Through the main character, Feng, Wong explores the cyclic nature of betrayal. A character who makes his living by convincing others that, surely, there must be someone they want killed, is from the very start both a victim and perpetrator of this corrosive force. As it turns out, Feng’s contempt for human life stems from a very intimate betrayal in his past.

Blindness in various forms appears throughout Ashes as both a consequence and a saving grace from this vicious cycle. There is the blind swordsman, who wants to make the most of his remaining vision while he still has it; the swordsman who practices against his reflection; the blindness to the consequences of actions. A wine which has the power to make a person forget his past is seen throughout, as one of the characters offers that, “Man’s biggest problem is that he remembers,” or else, every day could be a new beginning.

However, some people refuse this form of blindness, a gesture symbolic of the unwillingness to forget past betrayals and driving pains. These malignant forces have become their only form of sustenance in the desert. Each character, at least initially, acts in spite of others, a rejection or reproach for human decency. A consequence of betrayals, it is better to hurt than to be hurt.

However, many of the characters find their way out of this blindness, either through love or some act of humanity. In the end, there is redemption from this such spiritual deprivation and isolation. The desert becomes a symbol of self-exile, in which character come to reflect upon how their life choices have led them to where they are, physically and metaphorically.

Ashes of Time purports to be a story about vengeance, but as that cycle has no end, the film must have a more decisive meaning. Ultimately, then, the film is about how one comes to terms with his or her burdens, and closes the gaps of the past. It is about the perspective with which that individual looks forward. As one character wonders what could beyond the distant mountains, another answers, “another desert.”

Feng’s refusal to look into a different future is his ultimate failure; he condemns himself to the desert. He longs for the past, the opportunities, mistakes, and regrets gone by. This is the greatest connection Ashes establishes to the rest of Wong’s body of work. However, where Wong’s other films deal with these themes in modern settings in which characters sit idly by and dwell on the past through their daily activities, Ashes is much more understated in its presentation.

The desert setting demands survival; it fosters a preoccupation with actions, and illusions. While people in contemporary Hong Kong are free to fully embrace their emotions behind closed doors, the deserts of Ancient China manifests mirages of necessity, a blindness toward one’s inner life.